The United States has a long history of internal migration that influences the demography of states today. Most historical instances of voluntary migration were tied to the promises of a better life for those who moved. From the Homestead Acts, which promised 160 acres of land to anyone capable of developing the land, to the Great Migration, where millions of Black Americans moved north in search of better prospects, American history mythologizes moving to faraway places as a mechanism of self-improvement and rugged individualism.

“Bleeding Kansas,” or the period of violent clashes in the Kansas Territory that immediately preceded the Civil War, stands out in American history as a rare example of a time when migration happened explicitly to change the demographic makeup of a given population. It is a unique example of political migration.

Popular Sovereignty and the Kansas-Nebraska Act

In the early 1850s, some Democratic politicians were looking for a new way to allow for a “middle ground” on slavery that would create more flexibility than had been allowed by the compromises of previous decades. They came up with “popular sovereignty,” or the idea that the residents of new states and territories should be able to decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery regardless of what was designated by federal laws. In the 1850s, the overwhelming majority of people with voting rights were white men.

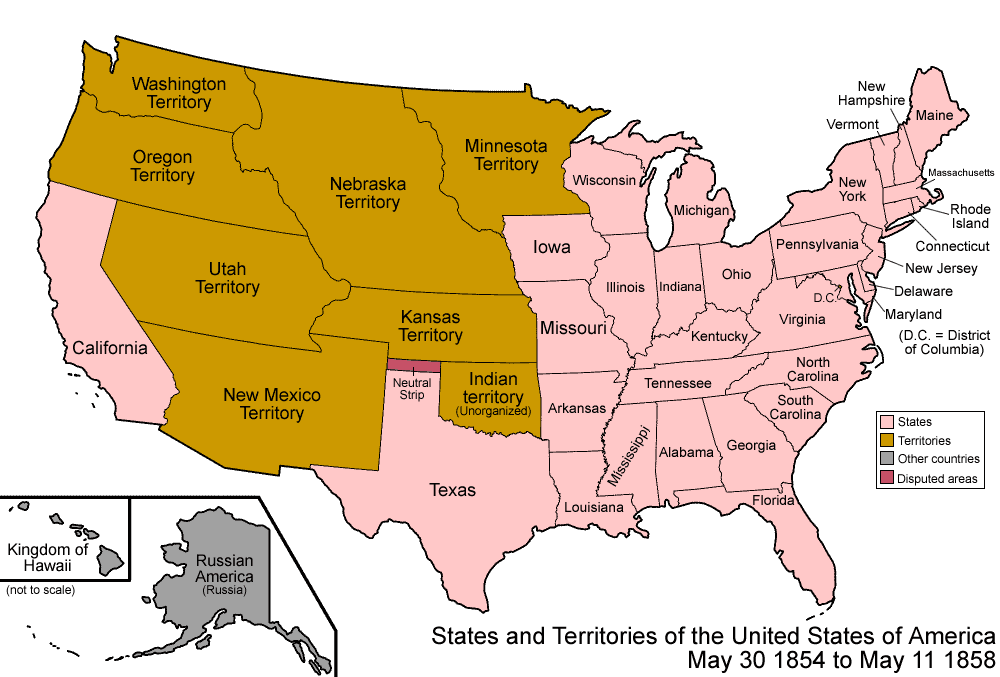

Though popular sovereignty was strongly opposed as a doctrine by some anti-slavery politicians, it was eventually codified by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which created new Kansas and Nebraska Territories that would decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery. These territories were both north of the latitude line established in the Missouri Compromise as the dividing line between free and slave states. Under that federal law, both territories should have been free states; the Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise.

Migration to Kansas for Political Reasons

As soon as the Kansas-Nebraska Act was enacted, migrants from other U.S. states immediately began moving to the area to influence voting outcomes on slavery. Nebraska was further north and shared no borders with slave-owning states; while the question of slavery remained contentious until it was ultimately outlawed in 1861, slavery never had a major footprint in the Nebraska Territory.

Kansas, on the other hand, shared a border with slave-owning Missouri and quickly became a major focal point for clashes about slavery. Nearly 100,000 people moved to Kansas in the period of 1855 to 1860. Many of these migrants came from Missouri, where slave-holders feared yet another free state on its border to which escaped slaves might flee. But politically-minded migrants came from all over the country to influence the outcome of popular sovereignty. The chance to influence the election was a pull factor that was the reason for political migration to Kansas.

Conflict arose quickly. The Kansas Territory’s election in 1855 featured massive voter fraud, with armed contingents of Missourians crossing the border to vote in favor of slavery. They argued that the Kansas-Nebraska Act contained no requirements as to whether or not someone needed to own land in the territory to establish residency, and therefore vote: the intention to move to Kansas at some point in the future was all that was needed to vote in its elections.

Political Effects of Migration to Kansas: Pro-Slavery Won

Pro-slavery attitudes won in that election, and the anti-slavery contingent of the population was incensed. They called the new government the “Bogus Legislature” and set up their own state government in Topeka, which drafted a constitution that outlawed slavery. Unfortunately, President Franklin Pierce was sympathetic to slave-owners, and after much debate in Congress, ultimately recognized the pro-slavery government as legitimate.

This decision only inflamed tensions in the Kansas Territory. The number of anti-slavery migrants increased, with organizations like the New England Emigrant Aid Society formed by activists to help abolitionists move to Kansas. Following the discord of the 1855 election, Pierce and later President James Buchanan attempted to craft a number of “compromises” that would allow slavery to be curtailed in some senses but overall remain present in the territory. These attempts were rejected by abolitionist voters.

Clashes Over Popular Sovereignty in “Bleeding Kansas”

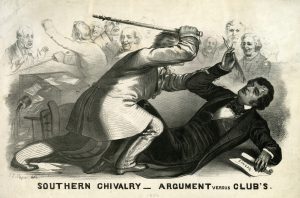

Ultimately, the conflict between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces erupted into violence. Militias formed on both sides of the conflict. In 1856, pro-slavery Missourians started by burning homes and business in Lawrence, Kansas. John Brown, the famous activist who himself had moved from Ohio to support abolitionist efforts in Kansas, then led his militia in a raid that killed five pro-slavery migrants. Soon after that, Senator Charles Sumner gave a speech in Congress denouncing slavery in Kansas and was promptly beaten nearly to death with a cane by Preston Brooks of South Carolina.

Ultimately, the conflict between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces erupted into violence. Militias formed on both sides of the conflict. In 1856, pro-slavery Missourians started by burning homes and business in Lawrence, Kansas. John Brown, the famous activist who himself had moved from Ohio to support abolitionist efforts in Kansas, then led his militia in a raid that killed five pro-slavery migrants. Soon after that, Senator Charles Sumner gave a speech in Congress denouncing slavery in Kansas and was promptly beaten nearly to death with a cane by Preston Brooks of South Carolina.

Violent clashes continued for the next several years, and ultimately, more than 50 people died as a result of “Bleeding Kansas.” The conflict was only resolved by the outbreak of the Civil War. When southern states seceded from the union, there were no longer any voices in Congress opposed to allowing Kansas to join as a free state. In 1861, Kansas became a U.S. state and abolished slavery.

Migration as a Political Tool

The Kansas-Nebraska Act and “Bleeding Kansas” will be forever remembered in American history as a flashpoint in the growing tensions that ultimately led to the Civil War. But it also stands out as an unusual phenomenon in the history of U.S. migration, where migrants viewed their settlement of a new territory as a way to enact their political will. “Bleeding Kansas” illustrates the many ways that demography and understanding populations can provide new understanding of events in history and beyond.

Images: Map (United States 1854-1858 by Golbez is licensed under CC BY 2.5), Preston Brooks caning Charles Sumner (The caning of Charles Sumner is Public Domain)