Each year in October, the second Monday of the month marks two separate occurrences. Although Columbus Day and Indigenous People’s Day share the same date, the different observances shed light on a narrative often excluded from U.S. history.

Indigenous Civilizations Before Columbus

Before 1492, little was known about the Americas to the outside world. Columbus was considered by many as the first to discover the “New World,” and it’s the reason he has been celebrated for years on his own day. But the reality is, the land was already being inhabited by over 600 Native American civilizations.

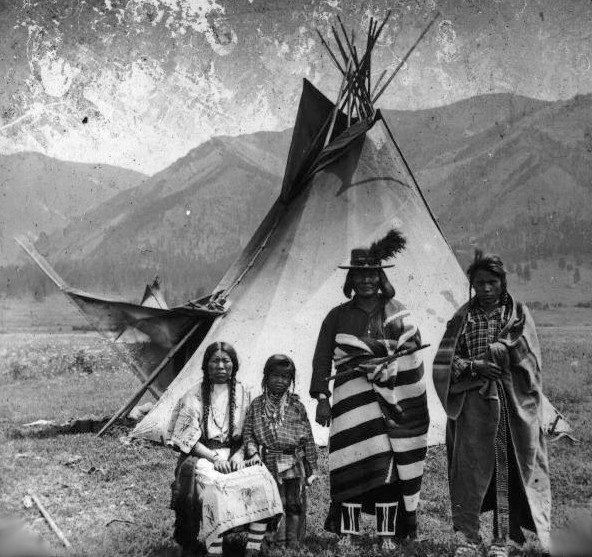

For over 20,000 years before the arrival of the Spanish in 1492, diverse Indigenous communities thrived and inhabited spaces across the Americas. Tribes could be found from Alaska, home to the Iñupiat, to the Caribbean where Taíno live, and beyond. In addition to rich spiritual practices, they also stewarded land with sustainable farming principles such as companion planting, crop rotation, polyculture, water harvesting, agroforestry, and more.

Despite the initial willingness of some Indigenous tribes to ally with Europeans, the widespread colonist view of Indigenous culture regarded them as savages and uncivilized. Indigenous populations began to decline rapidly due to the spread of disease, capture, and violence. Historians estimate that between 8 million and 112 million people inhabited the Americas before 1492. Throughout the 1500s, diseases such as smallpox spread to Indigenous tribes and caused widespread sickness and death, leaving less than 6 million Native Americans in 1650.

Forcibly Taking Land of Native Americans

Indigenous land started to become dispossessed after a series of treaties between the U.S. government and Native American tribes beginning in 1778. Eventually, President Andrew Jackson intensified the movement by urging Congress to pass the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

The passage of the Indian Removal Act began a gruesome and tragic decades long endeavor of forcibly removing around 100,000 Native people from their homelands to west of the Mississippi river. This was achieved through various treaties, military efforts, and private contractors that separated families, chained individuals together, and forcibly marched them away from their homelands and possessions.

The Trail of Tears and Other Forced Migrations

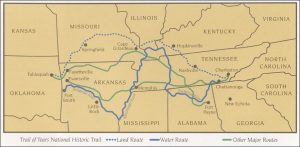

The Trail of Tears describes the displacement of five tribes (The Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole) from their ancestral homelands to Oklahoma. Individuals were forced to march on foot without food or supplies for 1,200 miles at times. It is estimated around 15,000 men, women and children died along the way. Today, the National Historical trail covers 5,000 miles across 9 states to commemorate the forced removal of Cherokee people from their homelands.

Similar names such as the “Trail of Death” have been given to other forced migrations, such as the Potawatomi Indians’ removal from their native land of Indiana to Kansas. The elderly and weak were forced to walk over 600 miles in extreme heat with a lack of water, which led to many fatalities.

The impact on populations cannot be understated, not only in numbers but also with the loss of cultural heritage, ecological stewardship, and ancestral knowledge. By 1900, the Indigenous population in the U.S. was at 237,000 compared to 600,000 the century prior. In addition to land displacement, stripping away Indigenous culture happened on a large scale in the late 1800s with the Carlisle school. Native children were stolen from their families and forced into assimilation. Out of more than 10,000 students who attended in its 39 years, only 158 graduated, and many died to due to disease and illness.

Lasting Impacts of Colonization on Native Identity and Land

There are few ways to reconcile the tragedy and violence experienced by Native American populations since the arrival of European colonists. Tribes have faced many generations of systemic oppression, displacement, and a lack of support from the government.

These generational effects have stripped Native Americans of their basic identity and cultural history, and had far-reaching impacts on social, emotional and physical health. While their ancestors had stewarded ecosystems in a sustainable way, much of present-day Indigenous existence has been destroyed or isolated onto barren, infertile lands. One study found that Indigenous communities across the United States have lost 98.9 percent of their original land. This displacement into lands that are often at higher risk for climate change impacts makes the communities even more vulnerable.

The Importance of Indigenous People’s Day

While we can’t erase the past, we can change the future. There are many ways you can honor this history, starting with the use and acknowledgement of Indigenous People’s Day. Some other ideas to get you started includes further education and reading about the Native American culture, supporting Indigenous businesses, adding land acknowledgments to your greetings, learning about Indigenous stewardship practices, and becoming involved with Native activist groups.

Image credits: Indigenous People’s March (2017 Indigenous Peoples March by Mike Maguire is licensed under CC BY 2.0); Family from the Flathead Nation (Flathead Family is Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons); Trail of Tears route (Trail of Tears map NPS is Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons); Dishchii’ Bikoh’ Apache Group from Cibecue, Arizona, demonstrating the Apache Crown Dance (Grand Canyon Native American Heritage Day 0307 by Grand Canyon National Park is licensed under CC BY 2.0)