The second blog in our series on invasive species in the United States, and will focus on the Kudzu Vine. Our first invasive species post focused on the spotted lantern fly.

Invasive Species Spotlight: Kudzu

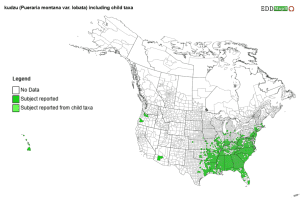

You have probably seen a mass of Kudzu vines covering trees, fields, rocks and powerlines if you have driven along highways in the southeastern United States. Also known as “the vine that ate the South,” Kudzu is an invasive species in the United States.

What is the Kudzu Vine?

Kudzu is a fast-growing semi-woody, perennial vine in the pea family. It has broad, lobed green leaves typically grouped in threes, giving it a lush, leafy appearance. Kudzu leaves can grow up to 8 inches in length while vines can reach 100 feet (approximately 30 meters). In late summer it produces clusters of fragrant purple to reddish flowers, followed by fuzzy seed pods. The vine often blankets trees, power lines, buildings, and railroad tracks creating a thick, tangled mass of vegetation.

Kudzu is a fast-growing semi-woody, perennial vine in the pea family. It has broad, lobed green leaves typically grouped in threes, giving it a lush, leafy appearance. Kudzu leaves can grow up to 8 inches in length while vines can reach 100 feet (approximately 30 meters). In late summer it produces clusters of fragrant purple to reddish flowers, followed by fuzzy seed pods. The vine often blankets trees, power lines, buildings, and railroad tracks creating a thick, tangled mass of vegetation.

Where Did the Kudzu Vine Come From?

This fast-growing vine, nicknamed “mile-a-minute vine,” is native to Japan, Korea, China, and several other Asian countries. It was first introduced to the United States during the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876 and was later showcased to southerners at the New Orleans Exposition of 1884-1886. It was marketed at the Japanese pavilion as a decorative ornamental climbing plant. And from the 1930s-50s Kudzu was promoted by the Soil Conservation Service (now the Natural Resource Conservation Service) as a cover crop to prevent soil erosion and as a forage for cows, goats, chickens, and even deer.

This fast-growing vine, nicknamed “mile-a-minute vine,” is native to Japan, Korea, China, and several other Asian countries. It was first introduced to the United States during the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876 and was later showcased to southerners at the New Orleans Exposition of 1884-1886. It was marketed at the Japanese pavilion as a decorative ornamental climbing plant. And from the 1930s-50s Kudzu was promoted by the Soil Conservation Service (now the Natural Resource Conservation Service) as a cover crop to prevent soil erosion and as a forage for cows, goats, chickens, and even deer.

How Does Kudzu Hurt the Environment?

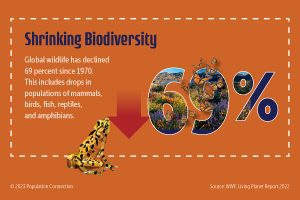

Kudzu is extremely invasive and outcompetes other plants by shading them and blocking sunlight, which prevents photosynthesis. As a result, native species often die off, leading to significant losses in biodiversity. It’s rapid growth—spreading as much as a foot (30 cm) per day—allows kudzu to quickly dominate entire landscapes and form dense monocultures that crowd out native vegetation.

Much of kudzu’s success comes from its underground structures. Its roots can extend more than ten feet deep and can weigh up to 100 pounds (45 kg) storing large amounts of energy and nitrogen. Like squash plants, kudzu can also form new roots from stem nodes that touch the soil. Each new rooted node absorbs additional nutrients, fueling the vine’s remarkable ability to spread and regrow even after being cut back.

Because of its aggressive growth and environmental impact, kudzu is now listed as a noxious weed in 13 states across the country. In several states, including Texas, Illinois, and Washington, it is illegal to import, cultivate, or sell kudzu seedlings. Beyond its invasiveness, kudzu’s nitrogen-fixing abilities can disrupt the natural nitrogen cycle, affecting soil fertility, water quality, and overall biodiversity. It also serves as a host for the kudzu bug and soybean rust, a plant disease that threatens agricultural crops.

The Economic Impact: How Much does Kudzu Cost in Damage?

Across the United States, damage to structures, control efforts, and productivity losses related to kudzu are regularly estimated to fall between $100 million and $500 million annually.

- Forestry companies are paying approximately $500 per hectare (approximately $200 per acre) per year for five years to control kudzu infestations.

- Power companies are paying $1.5 million a year to manage kudzu by mowing fields to access equipment and removing vines from powerlines.

- Kudzu has invaded more than half a million acres of privately owned forested land in Mississippi, costing landowners upwards of $54 million dollars annually in lost timber sales.

Together, these figures highlight how kudzu poses a serious economic threat spanning forestry, utilities, agriculture, recreation (parks and scenic areas), and personal property. Without effective control, the financial burden of kudzu continues to mount across multiple sectors and regions.

How to Control Kudzu Vines: Be a Steward of Native Ecosystems

Controlling the spread of kudzu requires dedicated persistence. Here’s what some states are doing to combat kudzu and a few simple ways you can help, too.

State-Level Action Against Kudzu

States impacted by kudzu have taken various measures to control the invasive vine.

Mechanical: Mowing is used to help manage kudzu growth; however consistent and persistent mowing over several years is required to prevent regrowth. Root removal provides effective, but labor-intensive control. Prescribed burns can be a useful pre-treatment for other control methods, like chemical applications.

Chemical: Foliar herbicide is sprayed directly onto kudzu leaves until they’re fully coated, but the process must be repeated two or three times for best results. The cut-stump method involves cutting the woody part of the vine near the ground and applying herbicide to the exposed stump.

Biological: Kudzu bugs were first introduced to the U.S. in 2009. While they’re not highly effective, they feed on Kudzu stems and leaves. Grazing livestock such as goats, sheep, and cattle have been used to clear patches of the vine.

Monetary: States and counties have been granted funds to help tackle their kudzu infestations. Mississippi offers Kudzu Treatment Assistance Options that help landowners in Mississippi manage the costs associated with kudzu.

Individual Actions to Get Rid of Kudzu

Attempting to control kudzu may seem like an impossible task, but there are several ways each of us can help manage small to large infestations.

Cut Down and Dig Up: Trees Atlanta has a helpful guide to removing kudzu vines and roots, primarily aimed at homeowners and communities ready to tackle the vine.

Use Approved Herbicides: Check your state’s university extension service or forestry commission for a recommended list of herbicides that can be used on personal property.

Utilize grazing animals: Hire companies to deploy, goats, sheep, and other livestock to graze and reduce kudzu growth. This process will need to be repeated but is a great way to initially clear an area.

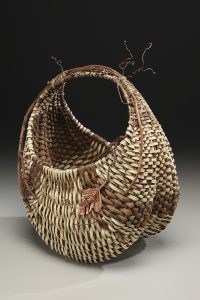

Get Creative: Collect vines to create woven items, like the Appalachian hen basket. Many parts of the plant are edible and can be enjoyed in desserts or as savory dishes.

Get Creative: Collect vines to create woven items, like the Appalachian hen basket. Many parts of the plant are edible and can be enjoyed in desserts or as savory dishes.

Plant Native Vines: While planting native vines will not directly stop kudzu growth, it can help restore ecological balance and reduce risk of future invasive outbreaks, as native plants support local insects and wildlife that naturally keep vegetation in check.

Stopping the Spread of Kudzu

Kudzu’s rapid growth and invasive nature have led many states to classify it as a noxious weed, prohibiting its import, sale, and cultivation. Despite these restrictions, millions of acres across the United States remain overrun by this persistent vine. A coordinated effort, combining state-led programs and individual management, can yield meaningful progress to combat the invasive kudzu, though sustained effort over several years is often required.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Kudzu Vine

How fast does the kudzu vine grow?

Kudzu is known for its extreme growth rate, expanding up to one foot (30 cm) per day during the growing season. This rapid spread is what makes the kudzu vine one of the most aggressive invasive plants in the United States.

What does the kudzu vine look like?

The kudzu vine has large, lobed leaves grouped in threes, long trailing vines that can reach 100 feet, and purple, grape-scented flowers that appear in late summer. It often blankets trees, powerlines, and buildings in thick green layers.

Why was the kudzu vine introduced?

The kudzu vine was introduced to the United States as an ornamental plant in 1876 and later promoted as a solution for soil erosion control and as livestock forage. What seemed helpful at first quickly became an ecological problem.

Where did the kudzu vine originally come from?

The kudzu vine is native to Japan, China, Korea, and other parts of East Asia, where it grows naturally and is used in food, fiber, and herbal medicine.

How did the kudzu vine get to America?

Kudzu arrived in America during the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, where it was showcased as a beautiful ornamental plant. Later, government agencies promoted it for erosion control, leading to its uncontrolled spread.

Image credits: Kudzu closeup (Pancrat, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons); Dairy cows eating kudzu in the 1950s (Columbus Public Library, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons); Kudzu root (Forest & Kim Starr, CC BY 3.0 US, via Wikimedia Commons); Map of Kudzu spread (EDDMapS. 2025. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia – Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed December 15, 2025.); Hen basket made of Kudzu (Mjtommey, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)