The infamous term “gerrymandering” originates from an 1812 incident in Massachusetts where Governor Elbridge Gerry re-drew district lines to benefit his political party. The oddly-drawn district resembled the shape of a mythical salamander, which, combined with his last name was branded “Gerrymander.” Since then, gerrymandering has plagued the U.S. redistricting process at every turn. In this blog, we will examine the long and fraught history of gerrymandering from basic redistricting laws, to the Civil Rights Act of 1965, and possible solutions to create a fair redistricting process to improve democracy.

Redistricting and The Census

On paper, redistricting sounds easy. Following the decennial census, states re-draw district lines to reflect the changes in populations over the past ten years. While these districts include elected officials at the state and local level, we are going to focus on the 435 national congressional districts that comprise the House of Representatives.

Each congressional district contains between 523,028 (Rhode Island’s Second District) and 1,023,579 (Montana’s first and only District) residents. Redistricting takes place every ten years after states receive the census data. As populations change, district lines occasionally need to shift to keep relative equilibrium with one another. For example, if over the course of a decade, many people move from one place to another, a state could find itself with one of its members of congress representing significantly more residents than another member. However, population changes are not the only reason a state may choose to change district lines.

Partisan gerrymandering occurs when district lines are drawn to give one political party or group an advantage over another. If a state’s majority changes political parties, the new majority often chooses to redraw district maps to include more favorable results in future elections. After the 2010 mid-term elections, Republicans swept hundreds of down-ballot seats across the country. Since 2010 was also a census year, the new Republican majorities in these states manipulated congressional districts to favor their party. It wasn’t until eight years later that Democrats performed well enough to regain control of the House of Representatives despite having majority support in many of the same states.

How to Gerrymander: Cracking and Packing

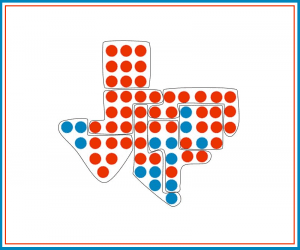

A common goal for a political party during an election is to maximize the number of voting districts in which your party can garner approximately 55-60% of the vote. If you do this, you are likely going to “win” the greatest number of seats in Congress. In other words, you have a district comprised of 100% Republican voters, you are “wasting” 45% of your vote, which could be used in another district to help win another seat in the House of Representatives. This is why it is tempting for parties in power to manipulate districts through gerrymandering.

Partisan gerrymandering is not a one-sided occurrence. Both Democrats and Republicans have been accused of using tactics such as “cracking” and “packing” to give themselves an edge in future elections.

“Cracking” occurs when large populations of similar voters, say, Republicans, are split into separate districts, each containing more likely-Democratic voters. Had the population of Republicans not been split, they would form a majority and likely elect a Republican candidate to represent their district. Let’s say a Democratic-controlled state contains a large, Republican-leaning population that is grouped close together and could be its own congressional district. The Democrats in office could crack this large group of Republicans in half, and add the individual pieces to other, heavily Democratic districts on either side. Instead of having two Democratic districts and one Republican district, the gerrymandered maps would lead to three likely-Democratic leaning districts.

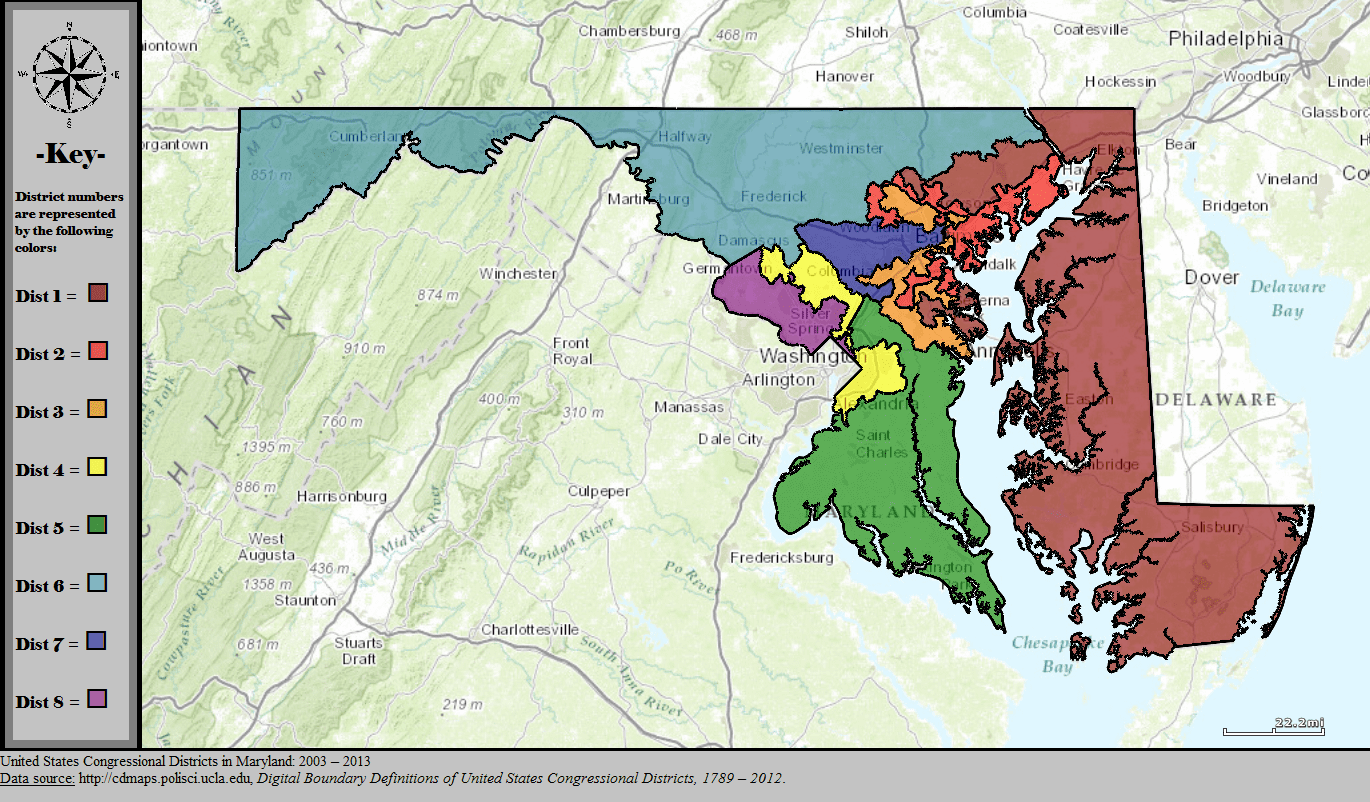

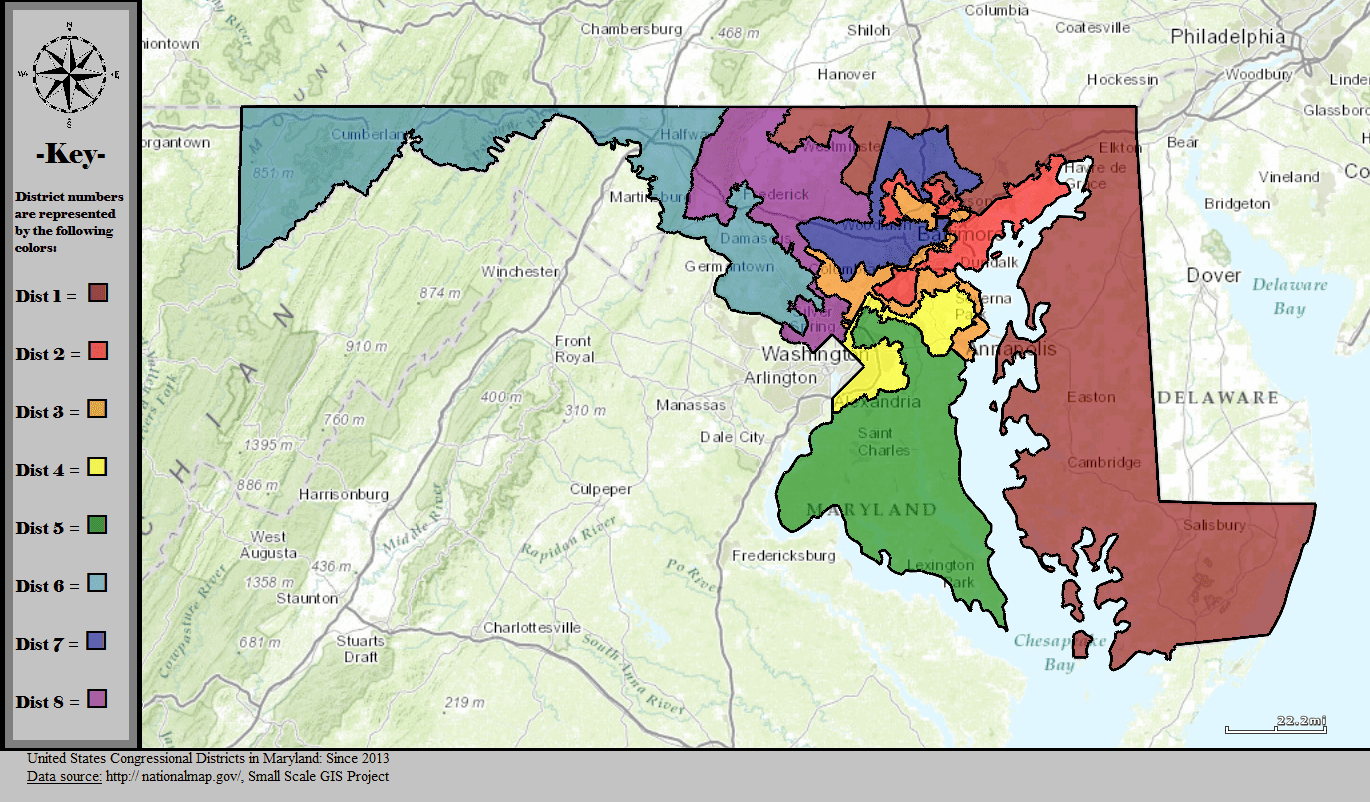

When Maryland Democrats re-drew the maps after the 2010 census, they cracked one of the most reliably Republican districts into multiple other districts, turning it, and surrounding districts blue. The changes were upheld in court and remain to this day.

1. Maryland’s congressional districts 2003 – 2013. Note District 6 is located in the top left of the state shaded light blue.

2. Maryland’s congressional districts 2013 – present. Note District 6 is located in the top left of the state shaded light blue.

“Packing” refers to the opposite tactic – grouping as many similar voters into one single district despite living in different areas of the state. This allows for only one super-majority district surrounded by multiple districts that now lean in favor of the party in power. For example, a Republican-controlled state could choose to consolidate as many likely Democratic voters into one district. While this would give Democrats one non-competitive House seat for years to come, it would also help the surrounding districts remain Republican-leaning, resulting in a net gain of House Republican seats for that state and the country at large.

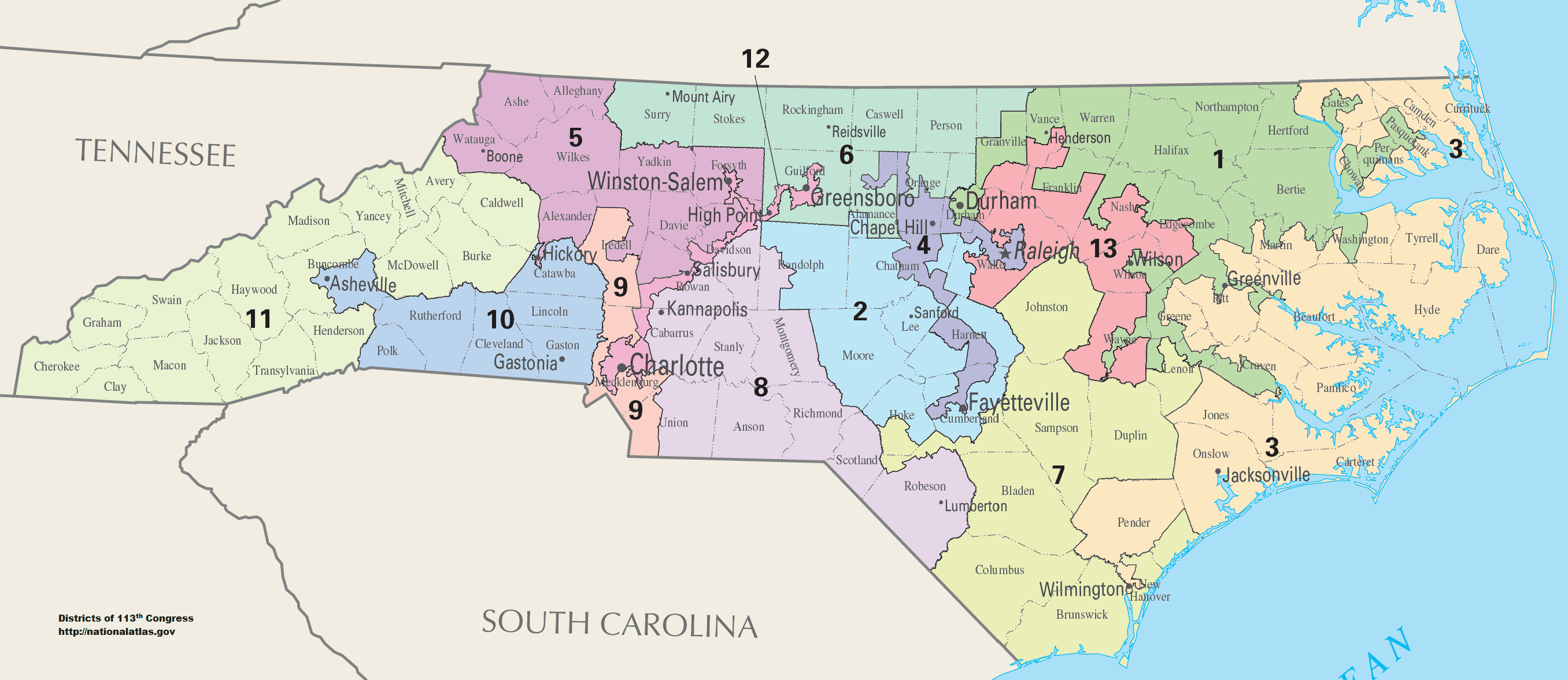

One of the most notorious examples of packing was North Carolina’s 12th District, which was thrown out in the courts on the basis of racial gerrymandering. North Carolina’s Republican-held state legislature created a district to pack as many Democratic voters into the same district, regardless of location. The district snaked along the middle of the state, intersecting or bordering five other districts.

Though packing can be interpreted as an unethical gerrymandering strategy, it is often a way for communities-of-interest to elect someone who truly represents them.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965: A Ban on Racial Gerrymandering

Unlike partisan gerrymandering, racial gerrymandering – intentionally drawing district lines to diminish the voting power of a protected minority – is illegal. Among dozens of other voter protections, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed racial gerrymandering. Maps that violate racial gerrymandering laws are challenged in court, and often thrown out. In the groundbreaking 1986 ruling Thornburg v Gingles, the Supreme Court released three criteria to prove racial gerrymandering is taking place:

- “The minority group must be able to demonstrate that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district.”

- “The minority group must be able to show that it is politically cohesive.”

- “The minority must be able to demonstrate that the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”

If these criteria are met, the map is thrown out and the redistricting process must begin anew. Thornburg v Gingles went further than to just protect minorities from racial gerrymandering. The law is also interpreted to legally create majority-minority districts which as of 2015 included 122 of the 435 congressional districts.

Majority-minority districts often look gerrymandered on paper because they can take odd shapes and are rarely deemed “compact.” However, these districts serve a crucial role in representing minority communities across the country. After the Thornburg v Gingles ruling, many newly drawn districts in the South elected their first African American representative since Reconstruction. Since then, Congress has seen incredibly positive gains with diversity, though there is still a ways to go before it represents the country as a whole.

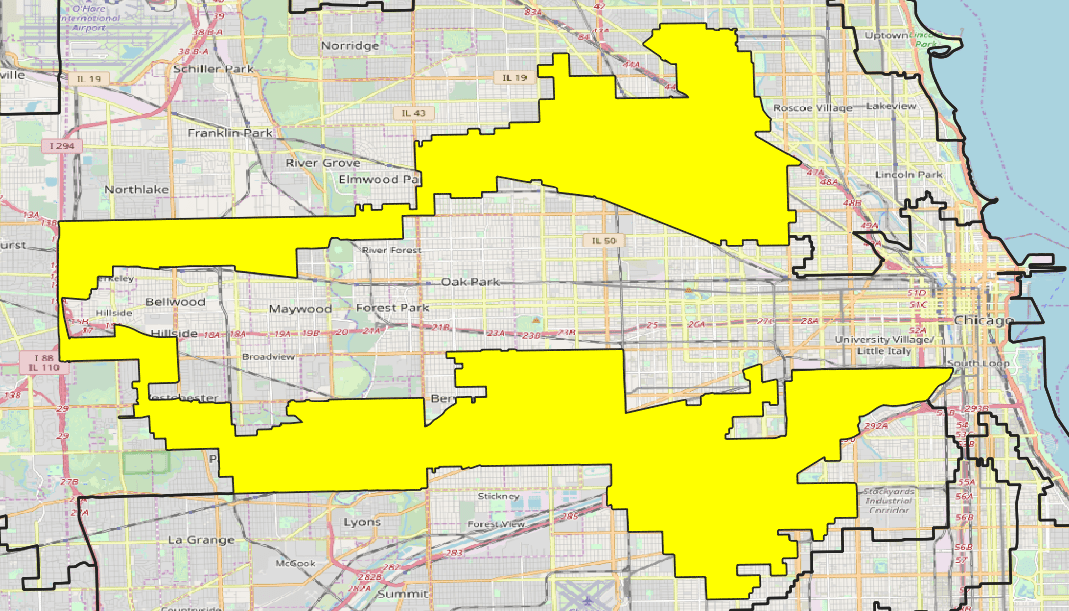

The 4th District of Illinois, commonly known as “the earmuffs,” is a perfect example of a strangely-shaped majority-minority district. The earmuffs give a voice to the large population of Latinx voters in and around Chicago, currently represented by Jesús “Chuy” García. The surrounding area consists of mostly Black and white residents. If the districts were drawn differently, the Latinx voters would not have a majority and their representatives would likely not look like the communities.

The 4th District of Illinois, commonly known as “the earmuffs,” is a perfect example of a strangely-shaped majority-minority district. The earmuffs give a voice to the large population of Latinx voters in and around Chicago, currently represented by Jesús “Chuy” García. The surrounding area consists of mostly Black and white residents. If the districts were drawn differently, the Latinx voters would not have a majority and their representatives would likely not look like the communities.

Despite the success of majority-minority districts, many Democratic officials are beginning to argue against packing people of color into the same district. Democrats fear that because people of color are more likely to support Democratic candidates than Republican, drawing majority-minority districts puts Democratic control of the House of Representatives at risk.

Angela Bryant, the former Chair of the Legislative Black Caucus in North Carolina, explains her decision to unpack her majority-minority district in 2017 on FiveThirtyEight’s “The Gerrymandering Project” podcast:

“I surely regret losing my district and the coalition that had been formed in that district. At the same time, the gerrymandering was a burden. I’m convinced that even if people like me lose out, to have a firm foundation upon which we are doing this redistricting, we will be better off over time.”

Bryant lost her seat in the re-draw of North Carolina’s state legislature districts.

Who Draws the District Lines?

It is clear that whoever draws district lines has a great deal of power over the outcome of future elections. Elected state legislatures are responsible for drawing congressional district lines in 31 states, 27 of which are subject to a veto from the governor. Many of the remaining states require an advisory commission or political appointee commission to draw the maps. Advisory commission maps must still be approved by state legislatures, allowing for ample partisan manipulation, and political appointee commissions are frequently chosen for the sole purpose of gerrymandering. However, in four states – Michigan, Colorado, California, and Arizona – independent commissions both draw and approve congressional district maps.

An Independent Solution to Gerrymandering?

Independent redistricting commissions sound like the saving grace for free and fair elections. The people who make up these commissions are not elected officials and are typically screened prior to their work by an independent entity to guarantee fair outcomes. In December 2016 the Center for American Progress released a report in favor of independent redistricting commissions stating:

“Independent commissions offer several benefits, including eliminating the appearance of impropriety and making elections fairer. Legislators, for instance, are four times more likely than independent commissions to create congressional districts that ‘deny voters choice in the primary’ and two times more likely to do so for general elections. This is perhaps one of the reasons why maps drawn by independent commissions face fewer legal challenges than maps drawn by politicians.”

If independent commissions are the answer to our country’s district-drawing woes, why doesn’t every state adopt them? The answer is relatively clear: states, and the politicians currently in office, do not want to give up their current advantage. It’s also the case that even when an independent redistricting commission draws the maps, voters are not always happy with the changes made, even if they are fair.

Following the 2010 census, Arizona’s booming population resulted in an additional congressional seat, requiring their independent redistricting committee comprised of two Democrats, two Republicans, and one Independent, to re-draw congressional maps. The commission used an outside mapping company to assist, and the approved maps made their first public appearance in 2012. A large portion of the public was absolutely outraged at the results.

Between 2000 and 2010, Arizona’s demographics had shifted dramatically, including a surge in Latinx and Hispanic communities. The Voting Rights Act protected these majority-minority communities, which leaned Democrat. These new variables combined with the state growing bluer among white voters created several left-leaning and newly competitive districts and forced two sitting Republican congressmen into the same district, requiring a highly competitive primary. The public outrage focused on the independent chairwoman, whom residents claimed was biased. The Governor acted swiftly and, with the help of the state legislature, impeached the commission chairwoman in a 21-6 vote. The maps were then challenged in court, though they were upheld and remain so to this day.

If independent redistricting commissions are also subject to accusations of partisanships, it is unclear if there will ever be a solution to gerrymandering, especially as the country grows more and more polarized. The sheer number of residents represented by a single person makes it nearly impossible for everyone in a community to feel truly seen.

Expanding the House

One solution is to expand the number of representatives in Congress. The arbitrary 435-member cap was only enacted in 1929, and previously the number of representatives grew alongside the population of the country. Expanding the number of total seats would make redistricting much easier, and could better reflect our diverse communities, truly representing the voices of the people.

The founding fathers anticipated a growing population and suggested that each House member should represent a district of 30,000 residents. Compared to our current average of 1:747,000, we are far from that ratio. Although a 1:30,000 representation may mean too many members (the House of Representatives would need roughly 11,000 members!), it would not be out of the question to at least continue to add some number of representatives with future population growth. Gerrymandering could still exist, but a handful of gerrymandered districts would not impact the overall representation of the country as it does now.

Gerrymandering has been a part of the United States for over two centuries now, and district maps are constantly challenged in the courts. But while we may not be able to choose the best way to draw the maps, voters are still able to make their voices heard. Recent elections have proved that the more citizens who choose to vote for their preferred candidate, the better democracy works – whether your district looks like a salamander or a pair of earmuffs.