Using historical case studies can be a great way to teach about environmental science phenomena like air pollution.

One such event was a deadly smog that gripped London in the early days of December 1952, causing mass hospitalizations, deaths and traffic accidents throughout the city. Many people today first heard about this event from an episode of the Netflix series, The Crown, which focused on how the royal family and Prime Minister Winston Churchill responded to the crisis.

Here’s a Synopsis of London’s Great Smog…

Here’s a Synopsis of London’s Great Smog…

Beginning in the 1870s, London acquired a new nickname – The Big Smoke – to describe the filthy haze that settled over the city as a result of all of the smokestack emissions from factories and the coal burning in homes across the city. It was this eerie gloom that served as a backdrop to many Victorian Era novels (think Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Bleak House).

Pea-Soupers

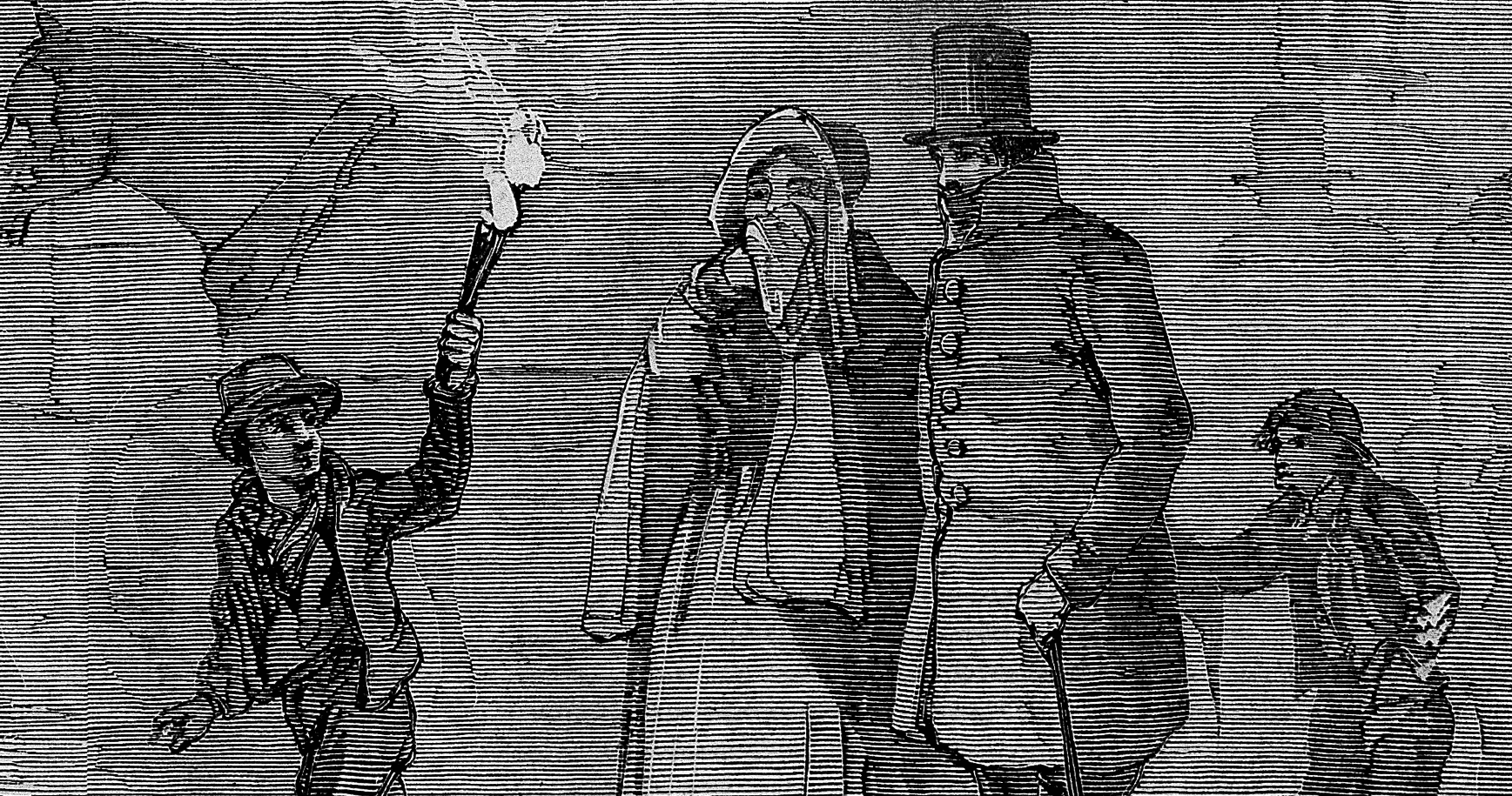

The resulting emissions contained soot particulates and sulfur dioxide. When combined with water vapor, this pollution created the iconic London fog. Drawings from the time portrayed Londoners covering their faces with handkerchiefs and donning “fog glasses” to prevent their eyes from stinging. These yellowish fogs of pollutants came to be known as “pea-soupers.”

Many decades later, researchers realized that the toxic sulfate building up in the foggy environment formed tiny droplets of sulfuric acid that can be blown around the city and breathed in by its residents. These droplets are the same composition as acid rain. But unlike rain, fog is easy to inhale, leading to respiratory damage and illness.

London’s pea-soupers continued well into the 20th century. In fact, emissions grew along with population rise. In 1840, London was already the world’s most populous city and home to 2 million people. By 1940, that number had swelled to 8.5 million people, none of whom could escape the risk of the pollution turning lethal if certain weather conditions occurred.

London’s Coal-Burning Power Plants Supplied Electricity, and a Deadly Fog

Fast forward to 1952. Now, in addition to emissions from industries, London’s air was affected by coal-burning power plants, supplying the city’s electricity. Cars and trucks (I mean “lorries”) now clogged the city streets and coughed out pollutants from their tailpipes. And, even though many other countries had transitioned to cleaner fuels, like natural gas, Londoners still relied on coal to heat their homes.

The weather had been colder than normal in southern England that fall. On December 4, a weather system known as an anticyclone settled over London. This weather caused a temperature inversion, meaning cold, stagnant air was trapped beneath a layer of warm air. With the smog trapped low to the ground, it mixed with the sulfurous coal that gave it an acrid smell and yellowish color. It covered the city for five days.

The fog caused widespread interruption for all modes of travel, and brought shipping in the Thames to a standstill. Conductors holding flashlights walked in front of double-decker buses to guide them down city streets. Pedestrians could barely see their feet as they tried not to slip on the greasy film coating the sidewalks. Even those who stayed inside were not safe. Smog seeped into buildings, including the Houses of Parliament, theaters, concert halls, shops and homes, smelling of rotten eggs and painting the walls with grime.

Deadly Health Impacts of London’s “Killer Fog””

Deadly Health Impacts of London’s “Killer Fog””

At first, city and country leaders downplayed the severity of what would later be described as a “killer fog.” Then hospitals began filling up with victims short of breath or injured in collisions from the low visibility. About 4,000 fog-induced deaths were reported in the days that followed – more civilian casualties than were caused by any single incident during WWII. An estimated 150,000 people were hospitalized with smog-related illnesses and injuries. As many as 8,000 more excess deaths in the months ahead were likely linked to the fog’s effects. The fog finally lifted on December 9 when wind from the west swept the smoky cloud away from the city and out to the North Sea.

Though slow to act, the British government did conduct an investigation into the causes of the “Great Smog,” which eventually led to the passage of Britain’s Clean Air Act of 1956. The Act restricted the burning of coal in urban areas, established smoke-free zones in the city, and provided grants to homeowners to convert their coal-fired stoves and furnaces to cleaner heating systems. The transition away from coal use took years, during which time more toxic fogs visited London, but none as devastating at The Great Smog of 1952.

Air Pollution in London Today

Coal was gradually eliminated from most UK homes and industries by the late 1970s and from the power sector by the beginning of the 21st century. So, no more “pea-soupers.” But the end of coal use didn’t spell the end of pollution in London. Vehicle exhaust has continued to plague the city. As recently as 2014, Oxford Street (a main shopping thoroughfare) was named the most polluted street on Earth, primarily due to the nitrogen dioxide (NO2) spewed from diesel vehicles.

That moniker wasn’t great for the city’s tourism. And so, London Mayor Sadiq Khan made air quality a top priority when he took office in 2016, establishing low (and ultra-low) emission zones, charging high fees for drivers with older (more polluting) cars, and installing lots of EV charging station. The city is aiming to reach net-zero emissions by 2030 – a 180-degree turnaround from days of “killer fogs.”

What London’s Great Smog of 1952 Taught Us

What London’s Great Smog of 1952 Taught Us

Seventy years on, there are lessons from the Great Smog of 1952 for other global cities. Many more newly industrialized cities depend on coal as a primary energy source today, creating the kind of sulfur dioxide emissions that led to London’s pea-soupers and acid rain. This is especially true in some of Asia’s largest cities, including Delhi, India and Lahore, Pakistan. In addition to emissions from coal-burning power plants and factories, the cities’ air is further tainted by the burning of crop waste from nearby farms.

And coal doesn’t only cause visible air pollution. It is currently the single biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions and phasing it out will be critical to meeting international climate goals. Britain has shown that countries can successfully transition away from coal, especially if cleaner and cheaper alternatives are available to meet people’s needs.

In the Air Pollution unit of PopEd’s high school curriculum, Earth Matters: Studies for Our Global Future, we include a case study about this event (“The Big Smoke: When London Fog Turned Deadly”), which also provides some useful context of the years leading up to it, beginning with the rapid industrialization of the 19th century in the UK. The reading also shows how the lessons learned changed fossil fuel usage, and what corollaries can be seen in rapidly industrializing cities today.

Image credits: London fog drawing (The Illustrated London News, volume 10, Jan. Wellcome Collection is licensed under CC BY 4.0) ; Policeman directing traffic (Image ID EJ7JFC Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy Stock Photo); Hybrid bus (Arriva London North HW3 LJ58 AVK rear 2 by Arriva436 is licensed under CC BY 3.0)