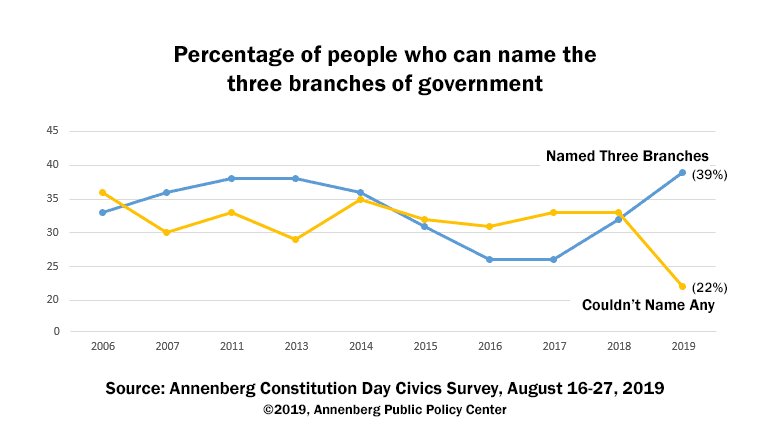

According to the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) annual polls, only 2 in 5 Americans (39%) can accurately name all three branches of government (Executive, Legislative, and Judicial, in case you are ever asked!). While this statistic is higher than previous years, it still causes concern. The APPC’s poll links adult knowledge of the Constitution and government specifically to the presence, or lack, of a high school civics education.

This blog post will explore what it means to have a quality civics education, how states are addressing the gap in civics knowledge, and what educators can do to create the next generation of empowered citizens.

Defining a Quality Civics Education

In many schools, there are no civic education courses at all. But where civics education courses are offered, the focus is often on memorization of facts, and not on the “engagement” and “skill building” that leads to both civic participation, and ultimately, to true interest in the subject.

Experts widely agree that a high quality civics education must instead include the four following:

- solid foundation of knowledge

- discussion of relevant issues

- interactive learning

- participation in the community

The Proven Practices Framework, which is included in the C3 Framework for Social Studies’ civics arc, goes further to detail specific civics teaching practices including discussion of current events, service learning, simulations of democratic procedures, news media literacy, and other participatory practices. This structure encourages educators to teach civics through a more participatory lens, rather than traditional measures, and focus on community engagement.

States Hold the Power in Deciding How (or If) to Teach Civics

Any civics-buff will be able to tell you that when it comes to education, the states hold the power. Adoption of education standards and curriculum are almost entirely left up to state and local governments, which leads to vast differences in civic education requirements around the country. In a 2018 report, the Center for American Progress compiled and analyzed civics education requirements for different states. The data showed that only nine states and the District of Columbia require a year of civics or government instruction in order to graduate high school. It is also these states that see higher levels of youth engagement, including youth voter turnout and community service than states with fewer, or no, graduation requirements around civics education.

Any civics-buff will be able to tell you that when it comes to education, the states hold the power. Adoption of education standards and curriculum are almost entirely left up to state and local governments, which leads to vast differences in civic education requirements around the country. In a 2018 report, the Center for American Progress compiled and analyzed civics education requirements for different states. The data showed that only nine states and the District of Columbia require a year of civics or government instruction in order to graduate high school. It is also these states that see higher levels of youth engagement, including youth voter turnout and community service than states with fewer, or no, graduation requirements around civics education.

Colorado in particular has one of the most robust civics education requirements in the country. In fact, the only statewide graduation requirement in Colorado is the completion of a civics and government course. Colorado designed curriculum for a full year civics course, and provides a myriad of resources and guidance for teachers on the subject. It is no surprise then, that in 2018 Colorado saw the third highest youth voter turnout in the country.

Beyond graduation requirements, many states have used non-profit resources to increase interest and quality of civics education. Generation Citizen, a nonprofit organization focusing on “action-civics,” implements a semester-long course at partner schools that uses a detailed curriculum based on local student interest. Students research a cause of their choice and find ways to get involved at a community level to make positive change. Generation Citizen, as well as other civic education non-profits like Mikva Challenge, highlight the importance of local partners and chapters to engage and empower our youth.

Student Activism on the Rise in the U.S.

Despite the dismal civics education policies at national and state levels, teachers around the country are finding ways to empower their students. In the past two years, the United States and the world as a whole has seen an unprecedented uprising of student activism. Following the Parkland massacre, students of all ages organized a nation-wide protest around gun safety in schools: March For Our Lives. Students around the world also participated in global climate strikes, famously led by 16-year-old Greta Thunberg.

Educators play a key role in this type of activism. First, students feel empowered when they have the space to do so. Allowing students the freedom to express themselves in the classroom is the most important step in fostering student activism. Secondly, students need to learn how the systems work so they can navigate the appropriate avenues for change. Instead of lectures on how a bill becomes a law, teachers can assign projects that include students reaching out to local officials, writing persuasive emails and letters to leaders in their community, or even to their congressperson. Encouraging students to take these small steps will give them confidence and know-how to interact with the government later in their lives.

While most policy makers agree on the need for more civics education in schools, teachers are not waiting for new laws and programs. Using resources from non-profit organizations and empowering students in the classroom every day, teachers are already creating civic-minded students who understand their role in society.

Image credits: Three branches of government graph (copyright 2019 Annenberg Public Policy Center); C3 framework logo (National Council for the Social Studies, C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards); Student with megaphone at climate march in Pittsburgh (ZeroHour-3-1090389 by Mark Dixon is licensed under CC BY 2.0)