After an extended period of remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it can seem like student engagement is at an all-time low, even among our highest achieving students. The pressures of an Advanced Placement course coupled with the stressors of teenage life in a post-pandemic world can severely undercut motivation in the classroom. As a former AP Environmental Science (APES) teacher in Washington DC, I totally understand. Incorporating the following five strategies into your APES classroom will allow you to maintain high student engagement throughout the entire school year.

1. Allow APES Students to Design and Test Their Own Research Question Early in the Year

Understanding experimental design is crucial for both sections of the AP Environmental Science exam. Set your students up for success by starting the year with a fully student-designed experiment. Provide some potential research questions and a possible materials list to jumpstart their thinking. Then let them do the rest.

When I conducted this activity in my APES classroom, I gave students potting soil, salt, sugar, radish seeds, inorganic fertilizer, and organic fertilizer. Each student group used this list to generate their own research question. They could use as many or as few of the materials to conduct their experiment as they wanted. Some examples of student-made research questions included, “How does the amount of fertilizer in soil affect the germination rate of radish seeds?” and “How does the density of radish seeds impact growth?” The best experiments included a large sample size and tested only one variable at a time. We dedicated about two class periods to planning and setting up their experiments. They took data every day for approximately two weeks and then wrote a lab report. (If you’d like to implement an acid rain lab test in the classroom using these materials, check our our high school Acid Tests resource.)

You can provide guidance, feedback, and scaffolds as you see appropriate. Ultimately, however, it should be student-driven – even if that means they make mistakes along the way. The mistakes they make are an integral part of the learning process. When students draft their lab report, they can identify ways to improve their experiment if they had the chance to repeat it. Were there variables they failed to control? Did they have a large enough sample size? Could they have been more meticulous in their methodology? If you have time to spare before the APES exam, it would be a fantastic exercise to revisit their experiments to reinforce the CED’s required science practices and concepts.

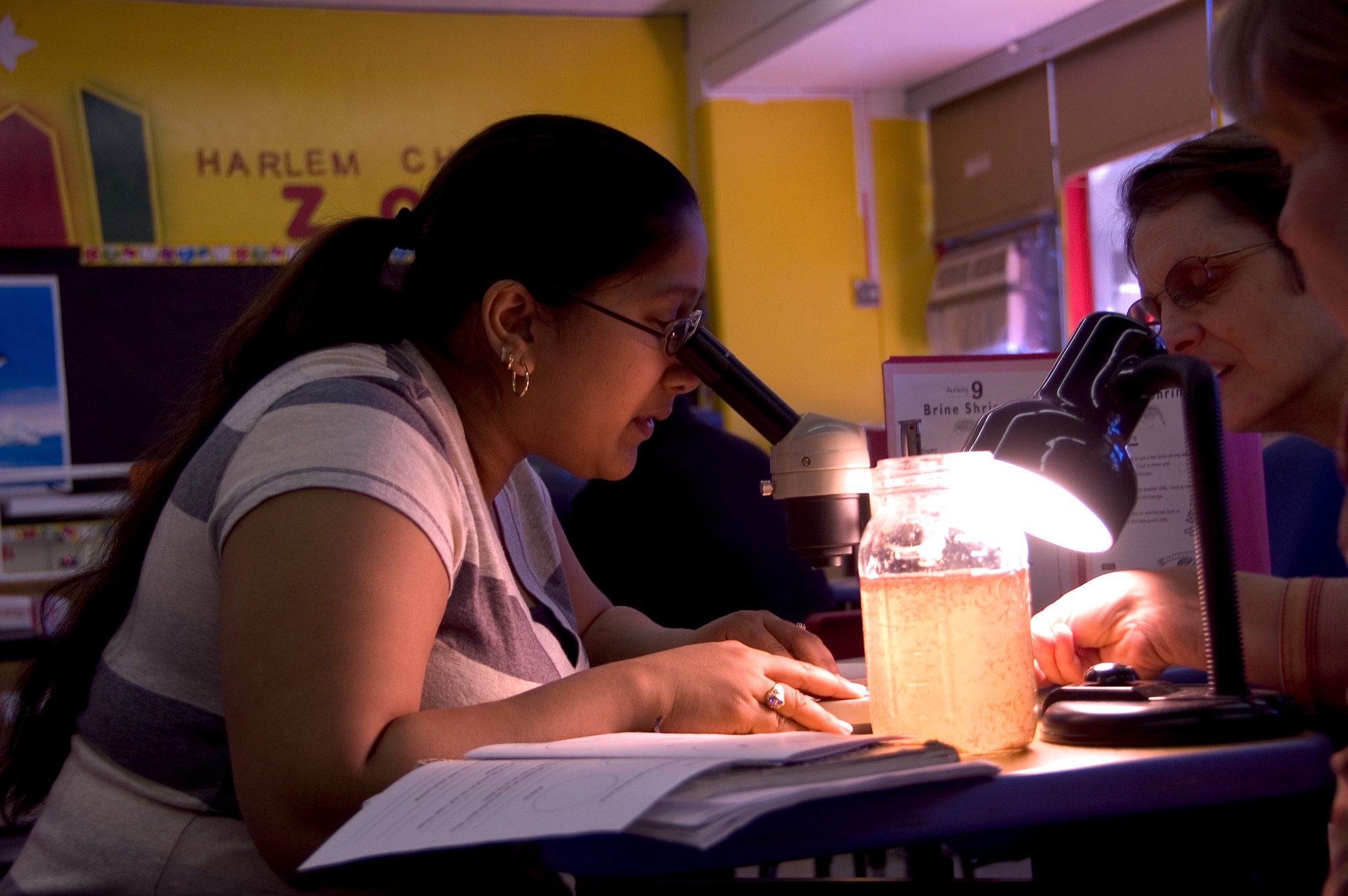

2. Use Live Specimens in Your APES Classroom

So much of what high school students learn exists in the theoretical. It is such a joy to bring the content to life – literally.

Brine shrimp, or sea monkeys, were a tried and true crowd-pleaser in my Environmental Science classroom. They are relatively inexpensive and can ship on short notice. Most importantly, they are adorable, tiny, and very much alive! There are so many experiment options that utilize brine shrimp. In my classroom, we tested their range of tolerance for a variety of abiotic factors – i.e. amount of light, pH, temperature, etc. Another favorite in my classroom was testing what concentration of herbal tea was lethal to 50% of our test population.

Of course, you can incorporate many other specimens into your APES labs. You can use guppies, snails, and duckweed in eco-columns, which are self-contained biospheres in a bottle. Maintaining eco-columns throughout the year will help reinforce concepts of nutrient cycling, water quality indicators, limiting factors, and more – all found in the APES CED. You can also use bacterial swabs on agar plates to demonstrate exponential population growth. The options are limitless, and it is a guaranteed way of ensuring full engagement from every student.

3. Weave Metacognition into Your APES Pedagogy

To ace the APES exam, students must have excellent testing skills in addition to being content experts. Throughout the school year, you should incorporate in-depth reviews of practice questions. It was a daily practice in my classroom to analyze each component of 1-2 tricky questions. Did the writers of this question include superfluous information? Are there any deceptive answer choices that sound like they could be correct but are not? How can we differentiate between deceptive answer choices and the correct choice?

If you make this type of metacognitive analysis a consistent practice, your APES students will begin to recognize some telltale patterns in multiple-choice questions. The more your students practice this skill, the more confident they will feel on practice quizzes and tests, and ultimately the AP Environmental Science exam.

4. Ask Questions That Don’t Have Clear Answers

Generating solutions to our most pressing environmental problems is a messy endeavor. For students to be prepared for the FRQ section of the exam (not to mention the real world), they must learn to grapple with complicated environmental problems. Not every question has an easy answer. How do we reconcile the need to alleviate poverty with the increased carbon emissions that result from increased affluence? Who is primarily responsible for environmental harms? Should we place more blame on the excessive consumption choices of individuals or on the corporations that produce these goods and services for consumption? What ecological policies are realistic given the hyper-partisan gridlock in Congress?

These questions have imperfect and subjective political answers. Even people within the same ideological umbrella do not agree on every solution. If you allow AP students to tackle nebulous questions, they will grow in their ability to generate fleshed-out, realistic possible answers.

5. Engender Hope in Your APES Students

It can be incapacitating to consider the consequences of the climate crisis. From the loss of human life to the loss of biodiversity, your high school students can become easily overwhelmed by the sheer breadth of problems. However, the worst possible reaction to this reality is surrendering to defeatism. If we let our students leave the classroom asking, “What’s the point?,” then we’ve done more harm than good. We don’t want to immobilize our students; we want to empower them.

Humans have a remarkable capacity to adapt and survive against all odds. Teach your APES students as many environmental success stories as you can. This will help nourish their interest in class topics, keeping them engaged rather than giving up. The good news is that there is no shortage of good news. The Montreal Protocol has all but restored the ozone layer. The growth of the global renewable energy sector has far outpaced prior predictions. Geoengineering solutions become more realistic every single day. Including these positive narratives in your AP Environmental Science pedagogy will foster a solutions-oriented mindset in your students.

APES Student Engagement

The most rewarding experiences in the classroom occur when you are able to spark your students’ intellectual curiosity and foster deep, authentic learning. From hands-on labs to higher order thinking strategies, these five tips are sure to keep your students engaged.

Image credits: Examining brine shrimp under microscope (Brine Shrimp by solarnu is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0); “No Planet B” march sign (Li-An Lim on Unsplash)