There was a time when many women around the globe, even in the richest countries, approached pregnancy and childbirth with fear because of the maternal mortality rate and knowing the high risk of often-fatal complications. In the early 19th century, more than 1 in 100 births in the U.S. and Europe ended in the mother’s death. Since the typical mother gave birth to 5-8 children, her lifetime chances of dying in childbirth ran as high as 1 in 12.

That was before our knowledge of infections (and how to prevent them), prenatal care, modern medicine, highly skilled doctors and midwives, and effective contraceptives. It seems like ancient history, but for too many women around the globe today, pregnancy and childbirth still come with unacceptably high risk. In fact, as of 2017, the share of women expected to die from pregnancy-related causes was more than 1 in 100 in 43 low and lower-middle income countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), almost 800 women die every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth.

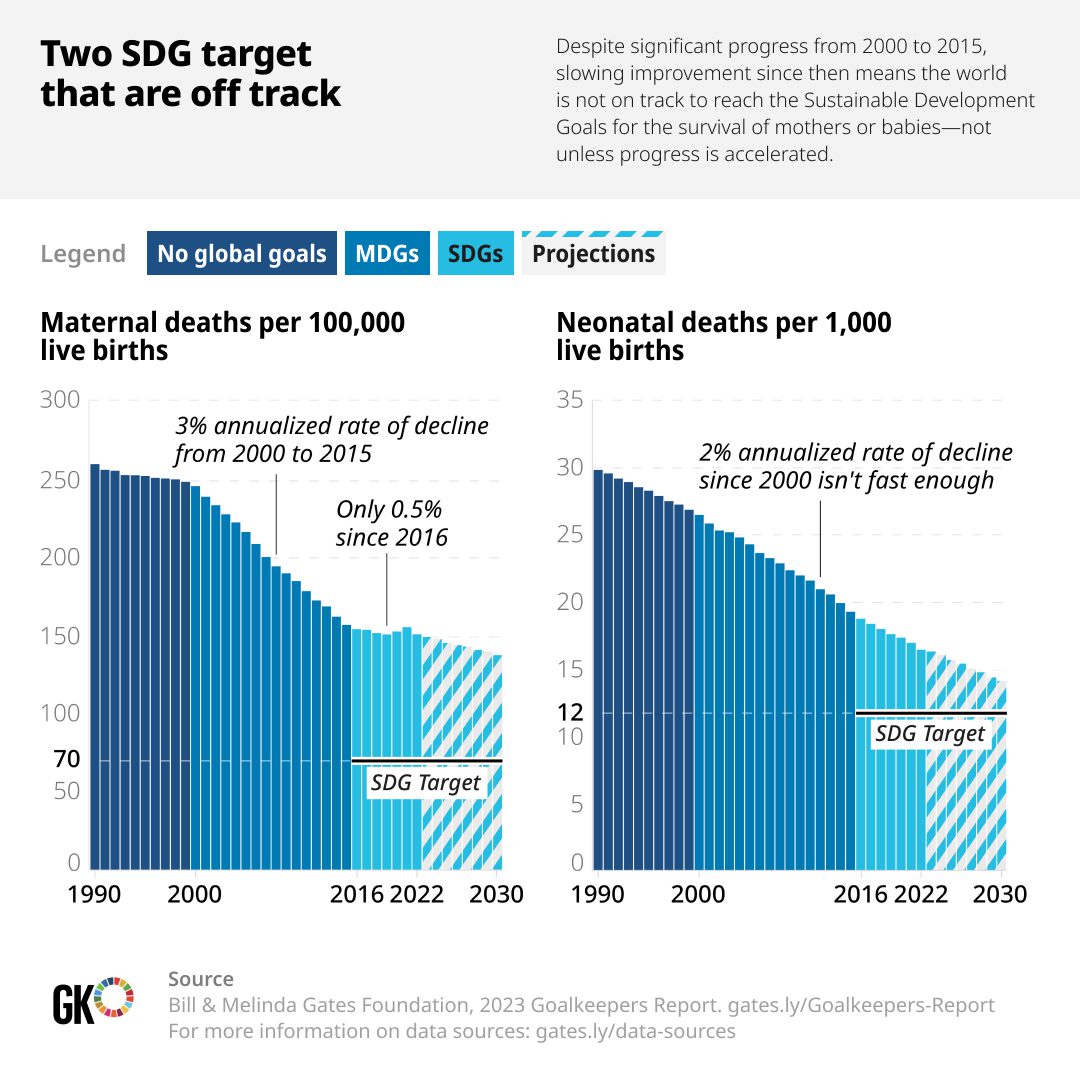

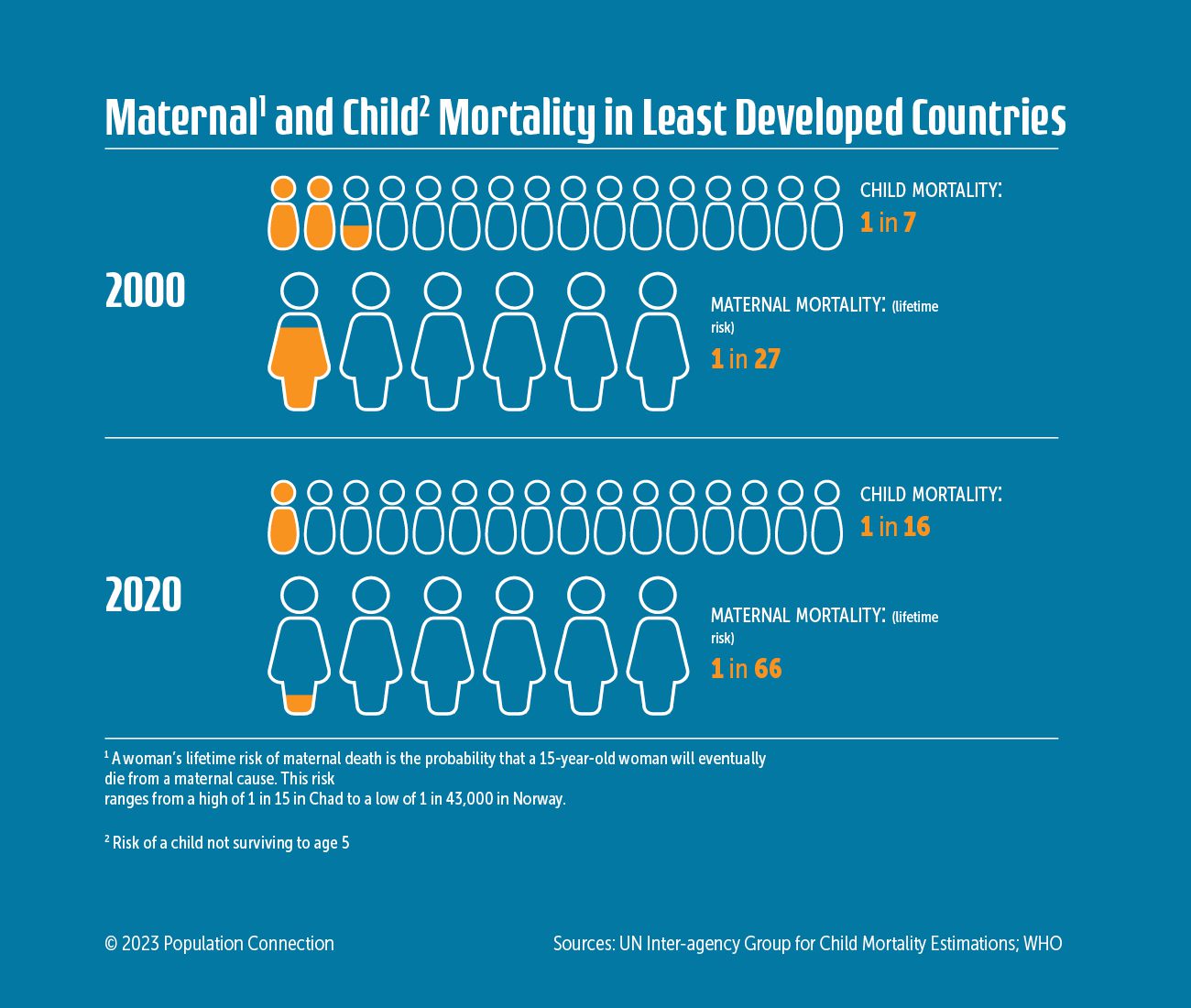

Major causes of maternal death include complications that occur during pregnancy (such as pre-eclampsia and eclampsia), following childbirth (such as infections and severe bleeding), as well as complications of unsafe abortions. Maternal mortality rates (MMR) declined by 34 percent between 2000 and 2020 – from 339 deaths to 223 deaths per 100,000 live births. While this progress is significant, it is far from the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3) of lowering maternal mortality to 70 per 100,000 by 2030.

Why is the Global Maternal Mortality Rate Still So High?

So, what is hampering this progress and imperiling the lives of so many women? Poverty and inequality substantially affect maternal mortality rates in low-income countries. Poor women often have the least access to prenatal care and skilled attendants during childbirth, due both to cost and geographic distance from hospitals and clinics for those living in rural areas. Poverty is also linked to maternal mortality through malnutrition, which can lead to chronic iron deficiency and anemia, making women more prone to hemorrhage and infections — two leading causes of maternal death. In many countries, entire health systems suffer from shortages of medical supplies and trained staff. The difference in average MMR between low and high-income countries is stark — 430 per 100,000 live births versus 12 per 100,000 live births.

Cultural beliefs and practices can also affect women’s reproductive health care. The WHO includes as a risk factor for maternal mortality “harmful gender norms and/or inequalities that result in a low prioritization of the rights of women and girls, including their right to safe, quality and affordable sexual and reproductive health services.”

Maternal Mortality in the U.S.

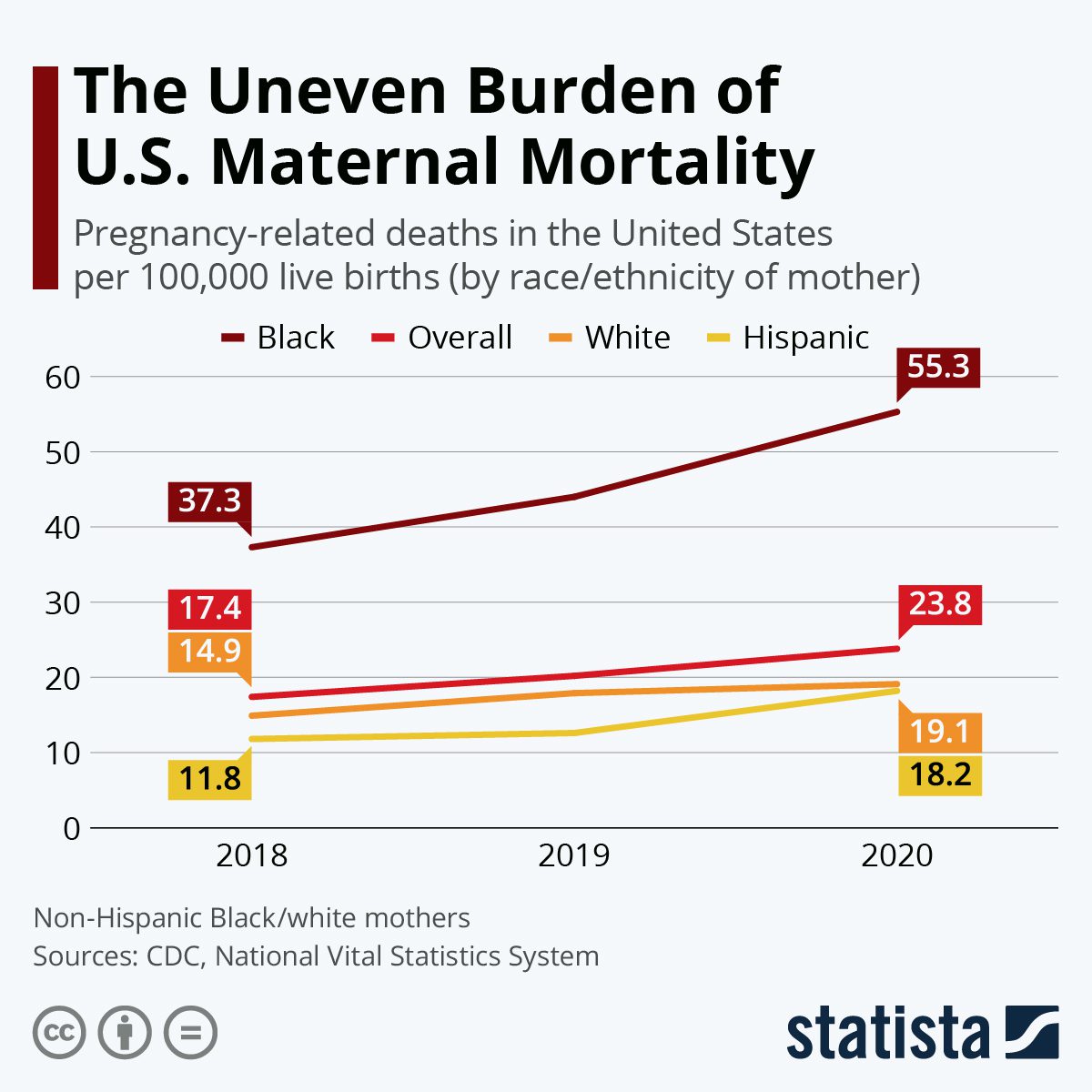

There are also challenges for women of reproductive age here in the U.S., which has the highest MMR of any high-income country. From 2018 to 2021, the U.S. maternal mortality rate nearly doubled from 17.4 per 100,000 to 32.9/100,000 according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This is triple the average rate of the 38 OECD countries – those with the most advanced economies. About 84% of pregnancy-related deaths are thought to be preventable, according to data from state committees that review maternal deaths.

Maternal Mortality Risks in the U.S.

Some trends that likely contribute to this increase include pregnancies at older ages when complications are more common, a rise in chronic health conditions in the population, and inequities in health care access and services. These inequities are related not just to socio-economic factors, but also race. Maternal mortality rates have risen for all racial groups in the U.S. over the past several years, but most especially for Black and Indigenous women, who are two to three times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes than White women.

The Impact of Race on Maternal Mortality

Black, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) women have higher shares of preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care compared to White women.

This is attributable, in part, to inequities in the U.S. health care system where many lack health insurance and/or access to quality health care due to location and income level. But a number of researchers are also identifying structural racism and implicit bias as contributing factors to the quality of reproductive health care women of color receive, especially given the disparities in MMR among women of different races who are in the same socio-economic group. This can manifest as less attentive treatment – or even mistreatment — by health care workers. It is also believed that the chronic stress related to societal discrimination can cause “premature biological aging” which can, in turn, affect health outcomes for mothers.

Abortion Bans and Maternal Mortality Rates

A recent factor that may affect reproductive health care in the U.S. is the banning of abortion, even in situations when the health and life of the mother may be at risk. This was a result of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade in 2022, considered settled law for nearly 50 years. As of January 2024, 14 states had banned all abortion and an additional 11 states had added restrictions, limiting availability.

Strategies to Reduce Maternal Mortality Rate

Reducing maternal mortality globally requires diverse interventions. Practices that would decrease maternal mortality include:

- Skilled Care During Pregnancy and Childbirth: Providing access to skilled healthcare professionals during pregnancy and childbirth has been shown to significantly reduce maternal mortality rates.

- Prenatal Care: Regular check-ups during pregnancy can help monitor and manage the health of the mother and the fetus, leading to better pregnancy outcomes.

- Postnatal Care for Mothers and Newborns: Ensuring that mothers and newborns receive appropriate postnatal care can help prevent and manage complications that can lead to maternal mortality.

- Family Planning Services: To avoid maternal deaths, it’s also important to prevent unwanted pregnancies and pregnancies among younger teens through contraception and sexuality education. Reproductive health care is an important part of overall wellness for the global population. An estimated 257 million women worldwide have an unmet need for contraception.

- Emergency Obstetric Care: Timely access to emergency obstetric care, including interventions to manage complications during childbirth, is crucial for reducing maternal mortality.

- Immunization and Infectious Disease Management: Interventions such as screening and antibiotic treatment for syphilis (a sexually transmitted disease), as well as immunization against tetanus, have been effective in reducing maternal mortality rates.

Examples of Decreasing Maternal Mortality

In their 2023 GoalKeepers Report, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation highlights innovative work being done by two obstetricians and researchers in sub-Saharan Africa to greatly improve maternal outcomes at minimal cost. These include better ways to diagnose and treat excessive post-partem bleeding, IV iron treatment that quickly treats anemia in pregnant women, and administering certain antibiotics at the onset of labor to reduce sepsis.

Additional interventions to reduce racial disparities in the maternal mortality rate in the U.S. might include improving training of health care workers to address unconscious bias, and encouraging more diversity among medical professionals providing reproductive health care. Universal health coverage and access could also narrow the MMR gap between the U.S. and other high-income countries.

Saving the Lives of Mothers

The world region with the lowest maternal mortality is the European Union, where only 6 women die per 100,000 live births. In today’s world where 136 million women give birth each year, if all countries had this level of maternal mortality, nearly 280,00 lives each year would be saved. Groups in the U.S. and around the world are pushing for greater awareness of maternal health issues, so that we can work toward this goal. In 2021, the White House recognized April 11-17 as Black Maternal Health Week, a campaign founded by the Black Mamas Matter Alliance. They are also part of a consortium of groups encouraging the United Nations to name April 11 as the International Day for Maternal Health and Rights.

Image credits: Pregnant belly (Pregnant woman and belly from RawPixel is Public Domain); SDG targets graph (Two SDG targets that are off track by Goalkeepers); Race and maternal mortality graph (The Uneven Burden of U.S. Maternal Mortality by Statista); Mother and child (Ibu Kurniasih dan Bayi Zahra Avra by USAID Indonesia is Public Domain)