Every summer Population Education is fortunate to host interns from around the U.S. These students bring their talents and passions to the PopEd program by completing a wide variety of projects. The following blog was written by one of PopEd’s 2024 summer interns.

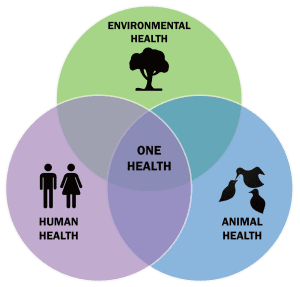

Currently, 60% of known infectious diseases and 75% of new infectious diseases result from zoonotic organisms. Pathogens from animals can spread to humans through direct contact, food, water, or the environment. Considering the connections between humans, animals, and the environment, researchers can explore how to use these interactions to improve collective health.

What is One Health?

One Health is a multisectoral approach to existing and future zoonotic health threats, implemented by global public health agencies. It aims to combine human, animal, and environmental health industries and resources to improve approaches to these threats.

Then and Now: The History of One Health

In 1964, veterinarian Calvin Schwabe introduced the concept of “one medicine”, which acknowledged the similarities between human and animal health disciplines. He suggested that veterinarians and physicians collaborate to solve global health problems. The One Health initiative then spread globally in the early 2000s due to the collaboration of numerous intergovernmental organizations, such as the World Bank, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Food and Agriculture Association (FAO). These notable One Health stakeholders worked together to create a document which provided nations with strategies to combat infectious diseases, particularly in areas where human-animal-environment interactions were high.

Following the establishment of the CDC’s One Health Office in 2009, One Health has continued to grow. The Quadripartite Organizations (a partnership between the FAO, WOAH, UNEP and WHO dedicated to One Health established in 2022) lead global efforts for promoting and supporting solutions that reduce zoonotic health threats. They are responsible for encouraging collaborative research on the impact of human activity on environment and animal species in critical areas, such as urbanization, food production, and trade. As of 2013, around 70 countries have shown interest in One Health policy development and approaches.

Challenges to the One Health Approach

Taking the One Health Approach from planning to action will be a challenge. Here are four areas that require focus.

1. Why Environmental Health Research is Key to Combating Zoonotic Diseases

The environmental health sector of the One Health triad has been the most difficult to research as its role in the interconnected health of humans and animals is often overlooked. The environment can produce either negative or positive effects on populations depending on the health condition of the environment itself. These effects are especially noticeable in bacterial ecosystems, which impact the pathogens that cause food insecurity, threaten water cleanliness, and compromise animal and human health. Considering climate change and other environmental stressors, it is critical that more research on understanding zoonotic diseases is conducted in a timely manner to prevent them from spreading. Such research will further involve the environment in One Health decision-making.

2. Empowering One Health Through Comprehensive Education Initiatives

Human, animal, and environmental healthcare workforces have different priorities and training. One Health initiatives would have to ensure that each workforce develops skills to collaborate across the three sectors. As One Health implementation efforts currently face the barrier of various understandings of its approach and framework, education can assist in clarifying and standardizing what One Health aims to accomplish. Involving education ministries into planning will better prepare health workforces to carry out One Health’s mission. Currently, there are 200 academic organizations around the world participating in One Health educational initiatives through research, curriculum and transdisciplinary training. Introducing One Health concepts, such as the intersectionality of health, health science collaboration and biological welfare, into STEM coursework at schools will grow a workforce capable of bridging critical gaps in the multifaceted approaches to zoonotic health threats.

3. Early Detection and Reporting: Keys to Effective One Health Implementation

Blood samples taken in Isiolo County, Kenya to test for brucellosis, Q fever and Rift Valley fever.

To implement One Health solutions, it is necessary to detect and share early zoonotic health risks. Detecting zoonotic diseases is difficult, considering the majority of them begin in rural regions that lack enough staff to surveil large areas, which affects real-time data collection. By increasing efforts in reporting and surveillance, outbreaks can be controlled and One Health can be better implemented. Currently, the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) is implementing the EBO-SURSY Project in West and Central Africa to strengthen existing detection systems for Ebola, Marburg virus, Rift Balley fever, Lassa fever, and the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. In Thailand, farmers and human and animal health officers use a mobile app called FARMER to report zoonotic diseases. Developed by the Bureau of Epidemiology, the app increases detection through reported threats to the Ministry of Public Health.

4. Addressing One Health Challenges in Developing Countries

The socioeconomic status of countries greatly impacts One Health approaches. As the demand for food grows alongside the growing population, nations that suffer from food insecurity are at greater risk of health issues due to malnutrition and contaminated food imports aimed at relieving malnutrition. Biosafety and biosecurity of imported products is important in ensuring zoonotic diseases do not spread. Additionally, urbanization, poverty, and migration increase the contact and transmission of zoonotic diseases. Overcrowded areas infested with rodents and lacking sanitation and waste disposal have higher vulnerability to outbreaks. Climate-threatened areas, particularly poor coastal and island populations with high occurrences of rain and floods, are also at risk of zoonoses like leptospirosis, cholera, and diarrhea. While new guidelines to support countries working to implement One Health continue to emerge, there must be global collaboration dedicated to uplifting developing nations so they have a reliable foundation to introduce One Health.

Benefits of the One Health Approach

While implementing One Health has its challenges, there are many benefits of its inclusion in modern health care practices. COVID-19 spotlighted the need for an improved, integrated surveillance system that holistically looks at causes for disease spread. One Health practices can help with pandemic prevention to avoid effects similar to the COVID-19 pandemic. The improved collaboration and communication between different health sectors can improve prevention strategies and accelerate research, detection, and responses. Additionally, One Health creates space for innovative ways to approach therapeutic treatments and medicinal approaches to needs that are currently unmet.

While implementing One Health has its challenges, there are many benefits of its inclusion in modern health care practices. COVID-19 spotlighted the need for an improved, integrated surveillance system that holistically looks at causes for disease spread. One Health practices can help with pandemic prevention to avoid effects similar to the COVID-19 pandemic. The improved collaboration and communication between different health sectors can improve prevention strategies and accelerate research, detection, and responses. Additionally, One Health creates space for innovative ways to approach therapeutic treatments and medicinal approaches to needs that are currently unmet.

The collaborative, multi-sectoral nature of One Health has the potential to reduce climate stressors, improve food security, and alleviate global communities of rabies and other zoonotic illnesses. Communication, coordination, and capacity building is necessary to further promote One Health as a reliable approach to diseases. By combining the expertise of human, animal, and environmental professionals, the One Health concept could revolutionize health care and approaches to future health threats.

Image credits: Zoonotic diseases infographic (CDC, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons); One Health triad (Thddbfk, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons); Blood samples (Vacutainers containing blood samples by ILRI is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); Covid vaccine (New York National Guard, Flickr, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)