Every summer Population Education is fortunate to host interns from around the U.S. These students bring their talents and passions to the PopEd program by completing a wide variety of projects. The following blog was written by one of PopEd’s 2025 summer interns.

In this blog, we’ll explore both the language loss in Indigenous communities and the continuous resistance against the erasure of Native languages.

The Rise of English as a Global Language

Today, English is taught in 142 countries as part of their national core curricula, with another 41 countries offering it as an optional course. English is increasingly viewed as the world’s “universal language,” a key to global success, and an opening to jobs, travel, and media. Of the over 8 billion people on Earth, approximately 1.5 billion people speak English. Of this, approximately 380 million people speak English as their first language and 1.1 billion have a working knowledge of the language.

Dating back to the 1700s, English has been the dominant language in the United States’ government, official documents, and daily life. However, as we were a country of migrants who all spoke various languages, it was said to be “undemocratic and a threat to individual liberty” to have an official language declared in the U.S. Yet on March 1, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order declaring English the official language of the United States.

But for Indigenous communities in the United States, English has often come at a devastating cost, replacing the languages that so beautifully carried stories, ceremonies, songs, culture, memories, and ancestral knowledge for generations. These languages are not just means of communication but rather expressions of identity and cultures, and many of them are disappearing.

A History of Erasure: Language Suppression in U.S. Boarding Schools

In the 19th century, new policies codified mistreatment of Indigenous culture for the approximately 600,000 Native Americans living in what we now know to be the U.S. The U.S. Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act in 1819, a law designed to promote the education and “civilization” of Native Americans. The act allocated money to Christian missionaries and the federal government to establish schools that would “assimilate” Native American youth and push for the abandonment of Native cultural practices.

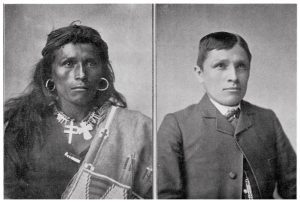

Tom Torlino (Navajo), “As he entered the school in 1882” and “As he appeared three years later” from Souvenir of the Carlisle Indian School, 1902.

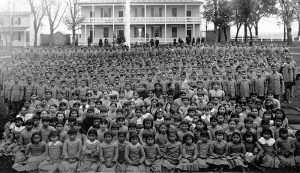

As a result of the Civilization Fund Act, the federal government introduced reservation schools in the 1860s which involved Native children attending school during the day but would return home at the end of the day. However, government officials felt that even a small connection to home was a barrier to assimilation, and these schools were not adequately “civilizing” these children. This led to boarding schools, also known as off-reservation schools, which removed children from their families and communities entirely. Students were forbidden not only from speaking their Native languages but also from wearing traditional clothing, hairstyles, and practicing cultural traditions.

“Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Captain Richard Henry Pratt, founder of The Carlisle Indian Industrial School

This chilling phrase became the guiding philosophy of these institutions and embodied the mission of these schools. By 1973, over 60,000 Native children had attended these schools, many of whom faced emotional trauma and cultural loss. Children were taught not only to reject their heritage but were often physically and emotionally abused if they spoke their Native language.

Trauma and Silence: How Indigenous Language Loss Was Passed Down

The documentary “Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools,” produced by PBS Utah, discusses the dark truth of the boarding school system and how the trauma of these schools didn’t end when the students left. Many survivors of these boarding schools were burdened by fear and shame and chose not to teach their own children their Indigenous languages. As a result of assimilation and issues such as mass migrations and lack of services, generations grew up unable to speak or understand the words of their ancestors. This gap led to Indigenous children describing feeling disconnected from their culture because of the language and culture loss that occurred. Today, one Indigenous language dies approximately every two weeks.

Pupils at Carlisle Native Industrial School, Pennsylvania (c. 1900)

Resistance and Revival of Native Languages

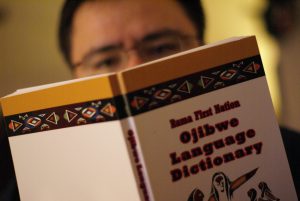

Previous analyses have made clear, it is extremely difficult to recover linguistic diversity for many reasons, especially the lack of documentation. However, many Indigenous communities in North America are fighting against these barriers and leading powerful movements to revive their languages and reconnect with their cultural identity. Reformed boarding schools such as the Santa Fe Indian School and language camps are honoring Native languages. They are providing Indigenous language preservation tools to students and communities to make it possible for new generations to learn, speak, share, celebrate, and reclaim their Native tongues.

Additionally, there are online tools for language revitalization that are able to reach people in all corners of the U.S. and help combat Indigenous language extinction. Here are some examples of digital resources that are helping teach, preserve, and share endangered languages.

- Online dictionaries such as the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary

- Websites such as this one created by the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma

The language loss seen within Indigenous communities in the United States is only a glimpse into the global issue of language loss and homogenization. The video “Vanishing Voices: Preserving Indigenous Languages for Future Generations” produced by News Central TV, revealed that 7,000 languages are spoken worldwide but, of those 7,000 languages, 45% of them are endangered. In Nigeria alone, more than 500 languages are spoken but only a fraction of those languages are included in the country’s education system, limiting cultural visibility.

Language revival is not just a form of communication but an act of resistance and healing. We must remember that when a language is lost, so is a way of seeing the world. Reclaiming these languages and diversity breathes life back into our communities.

Image credits: Attendees of the 2022 Standford Powwow, a student-run powwow in California (Suiren2022, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons); Tom Torlino (Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons); School photo (Frontier Forts, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons); Ojibwe language dictionary (Rama First Nation – Ojibwe Language Dictionary by Robert Snache – Spirithands.net is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)