What is Fast Fashion?

As sustainability becomes a more deeply held value in American society, the term ‘fast fashion’ has emerged in the public consciousness. Fast fashion refers to the business model in which trendy fashion items are rapidly produced in mass quantities. Garments produced by fast fashion brands are sold to the consumer at a low-price and are typically not manufactured to last beyond a few wears. Some of the biggest fast fashion companies include Fashion Nova, H&M, Forever 21, Gap, ASOS, and Inditex (the retail conglomerate that owns Zara).

This manufacturing method for fast fashion first emerged in the 1980s, as apparel companies faced pressure to release new clothing collections more quickly. Prior to this, there were generally two collection cycles each year. Now, many fast fashion brands release a “micro-collection” every other week. Since the year 2000, fashion production has increased by 60%. We are buying more clothes than ever and are getting fewer and fewer wears out the bargain. This paradigm shift has made shopping easier and more accessible than ever. However, there is an enormous environmental and human rights cost of this convenience.

Environmental Impact of Fast Fashion: Water Woes and Polyester Problems

The use of synthetic materials, such as polyester, has enabled the fashion industry to mass produce garments. Previously, manufacturers were limited by the amount of land that could be dedicated to growing cotton or raising sheep for wool. Polyester is cheap and easy to make in massive quantities. Not only does this result in more garments being created – which will ultimately end up in a landfill and generate scraps of fabric waste in the process – but it also results in more than twice as much carbon emissions per garment. Polyester is created using crude oil and generates approximately 5.5kg of carbon dioxide per t-shirt, compared to 2.1kg per cotton t-shirt. In fact, the fast fashion industry alone accounts for upwards of 10% of greenhouse gas emissions for the entire planet. That’s more than the carbon footprint of international aviation and maritime shipping combined. Furthermore, the fashion industry is on track to more than double that footprint by midcentury.

The negative consequences of polyester don’t stop there. Synthetic microfibers in our garments are non-biodegradable. Every time we wash and dry our clothes, microplastics enter waterways. An estimated 500,000 tons of microplastics enter aquatic ecosystems this way. Globally, we discard nearly 100 million tons of clothes or textile scraps each year, too. Collectively, that accounts for 85% of the textiles we produce each year. Between leachate from landfills or garbage dumped directly into the ocean, plastic from our clothes has several avenues to end up in our water. In total, fibers from synthetic textiles account for more than a third of the microplastics that end up in oceans and about 11% of all the plastic pollution in the ocean. Microplastics from textiles aren’t the only part of the fashion industry that contributes to water pollution. One fifth of the world’s wastewater results from textile dyeing.

As the fast fashion industry grows, the total environmental footprint will grow with it.

The Social Cost of Cheap Clothes: Low Wages, Safety Hazards, and Sexism

Fast fashion companies offer clothes at incredibly low prices. While this is great for the consumer’s bank account, the low cost of clothes is possible because of labor exploitation. Fashion companies outsource their labor to countries with incredibly lax labor laws in order to drive down the ticket price of their garments. Most clothes in the U.S. are made in Bangladesh, China, and Ethiopia. In Bangladesh, the average garment worker earns a yearly salary (adjusted for purchasing power parity) of approximately $3,300 USD. In China, that figure is approximately $6,259 and in Ethiopia it is $1,343. Unfortunately, the exploitation of garment workers goes far beyond just low wages. There is very little oversight in the factories where our clothes are made regarding worker safety. Many garment laborers work in dilapidated buildings with dubious structural integrity, often inhaling toxic chemicals from the production of synthetic textiles.

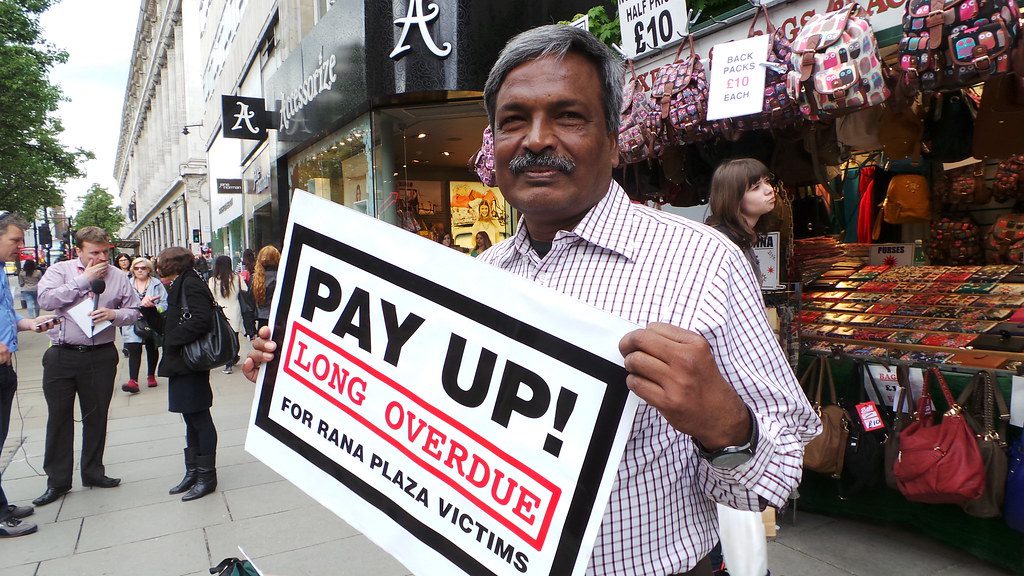

In 2013, the Rana Plaza garment factory complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh collapsed. Building owners were aware of the structural integrity issues in the factory, but ordered workers to return to the building despite the risks. The collapse at Rana Plaza remains the deadliest garment-related disaster on record, taking the lives of more than 1,000 people. Unfortunately, very little compensation was given to survivors or families of the deceased. Since Rana Plaza, more than 100 accidents have occurred at textile sweatshops worldwide.

Because garment workers are predominantly women and girls, the fast fashion industry contributes to some of the worst gender-based human rights violations in the world. Many female garment workers report facing sexual coercion, assault, and harassment while on the job. Women are frequently forced to take birth control and submit to regular pregnancy tests so that employers can avoid payouts for maternity leave. Some women even get fired for becoming pregnant. Unsurprisingly, women also risk termination or further harassment if they attempt to speak out.

How Can We Change the System?

Individual Action: The good news is that individuals can influence the system of fast fashion. We have agency in what we purchase. The idea of perfectly ethical consumption is impossible for any one person to attain. That doesn’t mean there aren’t more ethical consumption choices; it’s a spectrum, not a binary. Overconsumption is inherently a luxury. The most sustainable alternative to fast fashion and overconsumption just so happens to be the cheapest and most accessible option: what you already have in your closet.

Beyond buying fewer garments and wearing what you have for longer, there are a few other ways you can reduce your personal contribution to the fast fashion industry’s negative impacts. When making future clothing purchases, opt for versatile staples that are easy to incorporate into any fashion trend and only ever buy what you need. If your budget allows, invest in higher quality clothing options that will not fall apart as easily as cheaply made garments. Another more sustainable alternative is to buy second hand.

Systemic Change: While it is important to engage in conscious consumption, as individuals we can only do so much. This is especially true if one’s access to clothing options are limited to fast fashion companies due to financial or clothing size limitations. Fortunately, there are ways that we can support and encourage systemic change to the fashion industry, too.

One such avenue is the Bangladesh Accord, a legally binding agreement that apparel companies can volunteer to uphold. The Accord was created in response to the collapse at Rana Plaza to help address working conditions and building safety issues at garment factories in Bangladesh. Since the creation of the Accord, it has resolved thousands of safety complaints and forced tens of thousands of independent factory safety inspections to occur in Bangladesh. Brands that have signed on to the Accord include ASOS, H&M, and Inditex. Some notable companies that have not signed on to the Accord include Carter’s, Gap, Walmart, Amazon, and Patagonia. The Accord was renewed in August of last year, an extension which will last until August of 2023. When it is time for renewal, we can put pressure on apparel companies to commit to the Accord.

Legislation can also be passed to require transparency from clothing retailers or manufacturers who do business in the United States. In New York State, a bill is currently in committee called the Fashion Sustainability Act. This bill would require clothing retailers in New York to participate in supply chain mapping. Retailers would have to disclose detailed accounts of social and environmental impacts of their practices and what they are doing to mitigate those risks. If this bill passes and is enforced with some success in New York, there is the possibility that a similar bill could be written in the United States Congress.

Spreading Awareness About the Negative Impact of Fast Fashion

A lack of transparency about industry practices allows fast fashion brands to destroy the environment and commit human rights atrocities with impunity. The more awareness that exists regarding the fast fashion business model, the easier it will be to hold these brands to account. These companies have purposefully obfuscated the reality of their shady practices in order to keep customers in the dark. Instead, we should let there be light.

Image credits: H&M Storefront (Fast-Fashion giant H&M (world’s second-largest clothing manufacturer) #Logos of corporate behemoths by Dana L. Brown is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); T-shirts (AA by ElizabethHudy is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0); Sweatshop (Sweatshop project by marissaorton is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0); Rana Plaza protest (Rana Plaza disaster anniversary action on Oxford Street by Trades Union Congress is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)