The Endangered Species Act (ESA) has led to the protection of countless species and preserved millions of acres of wilderness and shorelines over the past forty-eight years. Signed by President Richard Nixon in 1973, the law has affected U.S. environmental protections for decades. However, the wide-ranging law has also been the source of significant controversy and in recent years, has been used to halt some sustainability projects, including those related to climate change, in their tracks.

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) has led to the protection of countless species and preserved millions of acres of wilderness and shorelines over the past forty-eight years. Signed by President Richard Nixon in 1973, the law has affected U.S. environmental protections for decades. However, the wide-ranging law has also been the source of significant controversy and in recent years, has been used to halt some sustainability projects, including those related to climate change, in their tracks.

In this blog post, we will explore the different ways the Endangered Species Act has affected environmental policy in the United States.

How the Endangered Species Act Works

The bulk of the ESA is summarized in three fundamental parts:

- Listing a species as threatened or endangered,

- Designating habitat essential to a species’ survival, and

- Restoring healthy populations of the species so that they can be removed from the list.

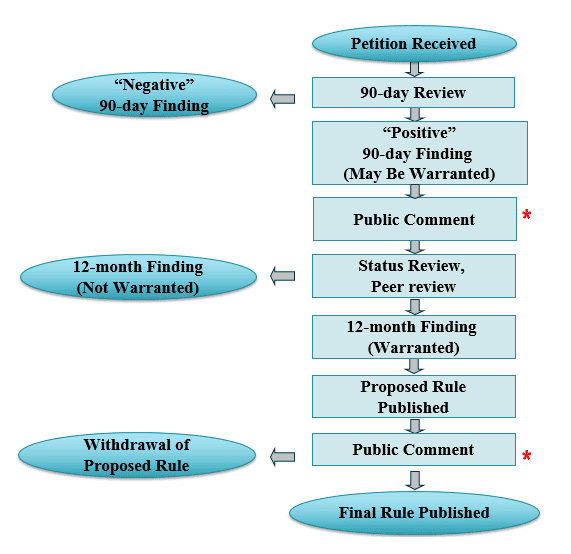

The power of listing a species on the endangered species list falls to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Typically, the USFWS receives a petition from a group of individuals or an environmental organization highlighting the need to protect an animal or plant that may be in danger of extinction. Once a petition is received, a series of peer-reviewed studies and opportunities for public comment occurs. This long process typically takes one year to complete before a final ruling is published – either classifying the species as “threatened” or “endangered,” or finding that the petition to list the species is not warranted.

The decision to list a species is a powerful way to enact change. Take the gray wolf case for example. Throughout the 19th century, gray wolf populations could be found all over the United States. However, as the United States’ population grew and expanded westward, people further encroached on the wolf’s territory and often hunted the animals to protect their own livestock. By 1967 studies estimated that there were fewer than 1,000 gray wolves living in the United States.

In 1978 – five years after the ESA was passed – the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officially listed the gray wolf as endangered. This listing meant that it was not only unlawful to hunt the wolves, but any development that would further degrade the wolf habitat would need to be halted. The impact of this listing was significant. Since 1978, gray wolf populations have rebounded, and as of 2021, the USFWS has counted over 6,000 gray wolves in the lower 48 states, allowing the agency to remove the animal from the endangered species list and classify it as recovered.

The Controversy Around the ESA and the Spotted Owl

While the largest threat to the gray wolf was direct trapping and hunting, most species face declining numbers less directly, due to habitat degradation. The ESA acknowledges and protects against human activity like dams, housing development, or logging within habitats that contain endangered or threatened species, though this often causes controversy among various stakeholders.

While the largest threat to the gray wolf was direct trapping and hunting, most species face declining numbers less directly, due to habitat degradation. The ESA acknowledges and protects against human activity like dams, housing development, or logging within habitats that contain endangered or threatened species, though this often causes controversy among various stakeholders.

One of the most well-known ESA controversies occurred throughout the 1990s around the listing of the northern spotted owl in the Pacific Northwest. In 1990, the USFWS officially classified the northern spotted owl as “threatened.” This classification meant that the owl’s habitat – which primarily consisted of old-growth forests – would need to be protected from human impact, including logging.

The northern spotted owl classification created politicized chaos first around the Pacific Northwest, and then nationally, as the controversy made its way into politics. Many logging companies claimed that the industry would need to lay off thousands of workers and the country would face supply chain issues without the ability to remove trees from the affected forests. Conversely, environmentalists argued that old-growth forests were already heavily depleted, citing a report that 76 percent of these forests had been logged since 1945 and the ecosystems needed the protections from the ESA. In the end, the ESA ruling prevailed, instituting protections for both the northern spotted owl as well as the old-growth forests still standing. While the rule of law remained intact, the northern spotted owl controversy created political animosity for the ESA that would echo for decades to come.

Is the ESA at Odds with Climate Protections?

Climate change was barely on scientists’ radar, let alone a household term, when the ESA was enacted. Now, the health of most species, including humans, is dependent on how much warming we can prevent in the next few decades. One would assume that the ESA would be a tool to combat climate change in the court systems. However, the hallmark law championed by environmentalists for over forty-eight years now finds itself blocking renewable energy projects – our best chance to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

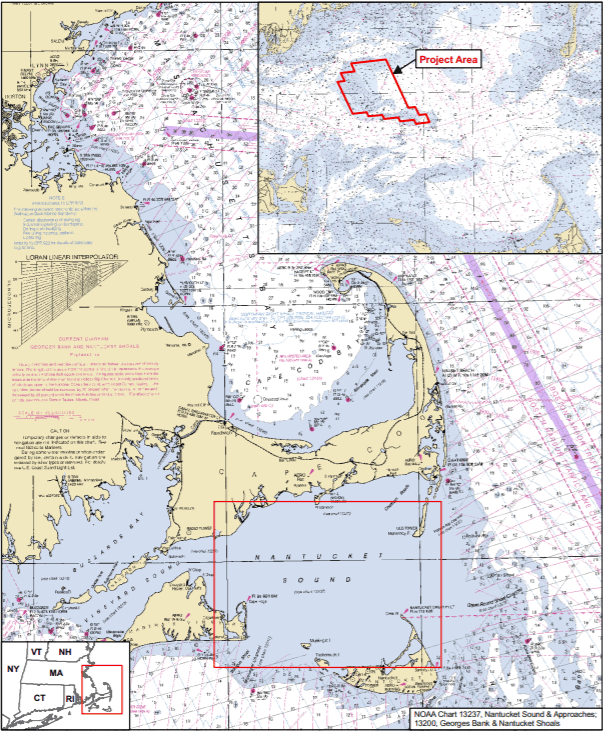

In November 2001, developers proposed a massive wind farm located off the coast of Cape Cod, MA called Cape Wind. The wind farm would be the first of its kind in the United States, encompassing twenty-four square miles of ocean, including miles of underwater power lines to bring clean energy to the mainland. Soon after the proposal went public, outrage and legal hurdles poured in. Many of the local lawmakers and environmental organizations that champion clean energy found themselves vehemently against the Cape Wind project, citing the harm it would bring to local wildlife like whales and migratory birds. Locals were accused of harboring NIMBY views (Not In My Back Yard), meaning that they only wanted to support environmental causes, as long as it did not affect their day-to-day lives, which often included unobstructed ocean views.

Cape Wind encountered numerous court battles over seventeen years, including multiple lawsuits arguing that the project violated the ESA. The large footprint of the project would have a lasting effect on the local ecosystem which is home to seven species classified as threatened or endangered by the USFWS, including birds, sea turtles, and most notably the North Atlantic right whale. Though these lawsuits were eventually thrown out, the ESA legislation was successful in delaying the project for more than a decade and cost stakeholders millions, eventually leading to Cape Wind’s abandonment.

The Future Role of the ESA

The Cape Wind case study illustrates the complicated nature of how environmental policy is used in the United States and around the world. The same law that saved the gray wolf from being hunted to extinction and preserved the dwindling old-growth forests necessary for the northern spotted owl, also halted a significant attempt to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The climate crisis will continue to threaten countless species over the coming decades. Some lawmakers are wondering if future ESA lawsuits will use the climate crisis as a basis for more clean energy projects, arguing that without increased action we will lose a significant amount of our biodiversity. It is clear the ESA has played a large role in past environmental policy, now it’s time to see how it will affect the future.

Image credits: Wolf (Gray wolf (canis Lupis) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters is licensed under CC BY 2.0); Listing a species diagram (How do you evaluate a petition you receive? by NOAA Fisheries); Owls (Northern Spotted Owl by Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington is licensed under CC BY 2.0); Cape Wind (A map of the proposed Cape Wind project, 2009 by the U.S. Department of Energy)