Anantapur District in Andhra Pradesh is one of India’s driest regions. It receives some of the lowest rainfall totals and is prone to frequent droughts. Over time, desertification took place – the poor soil combined with inadequate land management created a desert-like landscape that made supporting local economies a challenge. This is the story of how a community started a movement to restore the local ecology, repair depleted soil, and return a measure of economic stability to the region.

Anantapur District in Andhra Pradesh is one of India’s driest regions. It receives some of the lowest rainfall totals and is prone to frequent droughts. Over time, desertification took place – the poor soil combined with inadequate land management created a desert-like landscape that made supporting local economies a challenge. This is the story of how a community started a movement to restore the local ecology, repair depleted soil, and return a measure of economic stability to the region.

And with World Soil Day just around the corner – December 5th – what better way to celebrate than with a success story of reclaimed land.

A Soil Restoration Case Study

Part I: Desertification Turns Forest into Wasteland

Before the British occupation of India, the area around Mushtikovila village in Anantapur District contained expanses of mixed hardwood forests dominated by teak trees. The British harvested the teak trees in the 1860s to supply lumber for the exploding railroad network that crisscrossed the country. After Independence in 1947, local towns and villages continued harvesting trees. Within a few generations, much of the regions forests were cut down and gave way to scrub and grass lands.

Area around Mushtikovila, December 1999

Without a good tree canopy, the seasonal rains washed away valuable top soil. Wealthier landowners and higher caste families moved out of the region, and the management of the land fell to poorer, landless farmers who practiced subsistence farming and grazing. In the Mushtikovila area, farmers planted hardy grasses like millet and shared grazing land for small livestock. They communally managed the health of the ecosystem by rotating a variety of seasonal grass and grain crops and cycling in manure from the livestock.

In the 1970s, the Indian government changed land ownership laws and encouraged a shift from subsistence agriculture to cash crops. Instead of communally managing the land, individual farmers maximized profits by growing single crops, like peanuts, with intensive chemical use. This style of farming stripped away nutrients in the top soil and contributed to erosion. When drought hit, which it does frequently in this area, crops grown for profit failed. Another wave of landowners abandoned the area and left poorer, landless families to subside on a hardened earth with very little and unreliable water. This is a prime example of what typically happens when desertification occurs.

Part II: The Story of Soil in Mushtikovila

As the plants disappeared, the soil quality around Mushtikovila village declined dramatically. The unreliable rains dissolved natural salts in the soil. The salts were lighter than the surrounding minerals and floated up through the soil towards the surface. As the water evaporated, the salts formed a thick, impenetrable crust where seeds were unlikely to break through and take root.

Area around Mushtikovila, December 1999

At the same time, the water table fell. Trees no longer drew water upward through their deep roots. Without trees bringing water close to the surface, other plants with shallower roots, like grasses and shrubs, began to fail. Roots helped cycle nutrients and salts throughout the soil and kept the soil loose and aerated. Without deep-rooted plants, the salt crust grew thicker and more impenetrable and the water table dropped further. The Indian government classified the land that had been forest 150 years before as a revenue wasteland.

Part III: Restoration and Regeneration with the Timbaktu Collective

In 1990, Bablu Ganguly and Mary Vattamattam purchased 32 acres of wasteland and named the property Timbaktu. They had a goal: to restore the ecology of the degraded land using a minimal amount of money. They hired a forest watcher to patrol the property and prevent locals from harvesting or grazing plants. The forest watcher gathered and dispersed seeds from the hardy plants that took root in the inhospitable soil. These pioneer plants cracked through the salt crust, and made it possible for less resilient plants to take root. Slowly larger plants with deeper root systems sprouted, aerated the soil, drew water to the surface, and cycled nutrients up from below the salt crust. Natural processes began to turn back the decades of human impact under the watchful eye of the Timbaktu staff; the desertification was being reversed.

Mary Vattamattam and Bablu Ganguly

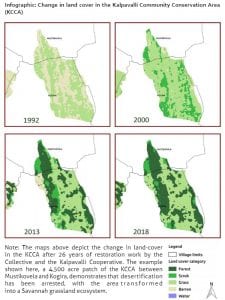

In 1992, Vattamattam and Ganguly shared the success of the Timbaktu ecological experiment with the surrounding community. They worked with a committee from neighboring Mushtikovila village to create a land management team to oversee 125 acres near the village. The committee called the communally protected area the Kalpavalli (“eternal source of abundance”) Community Conservation Area (KCCA). The team organized seedling plantings, rebuilt old water catchment systems, created firebreaks to prevent destructive wildfires, and organized teams of forest watchers to make sure local families harvested resources equitably and sustainably from the communally-managed land.

Within 10 years, the land turned green. Shrubs and trees took root and began to grow. Soil supported subsistence agriculture, animals returned that hadn’t been seen in generations, and the water table rose.

Within 10 years, the land turned green. Shrubs and trees took root and began to grow. Soil supported subsistence agriculture, animals returned that hadn’t been seen in generations, and the water table rose.

Now the KCCA encompasses 9000 acres of previously degraded revenue wastelands. It is likely India’s largest community-led ecological restoration initiative. Ecological surveys found the return of five large endangered mammals as well as hundreds of returning plant and animal species. Ten forest management zones monitor the sustainable collection of firewood, grasses for thatch and brooms, medicinal plants, and other flora and fauna used in nearby communities.

Part IV: Success with Soil Health and Beyond

As well as the KCCA, the Timbaktu Collective also oversees a wide variety of projects that improve the economic well-being of people living in the region and the ecological sustainability of the surrounding environment. They support a tuition-free, ecologically-focused boarding and day school for children from low income families, host seminars on organic and sustainable farming practices for local farmers, operate a business selling surplus produce from the managed lands, help landless laborers purchase and maintain small herds of livestock, create programming and advocate for children and adults with special needs, and promote alternative banking options and business cooperatives for women.

A waterway in the Kavapalli Community Conservation Area today.

Anantapur District is still one of the driest regions in India and prone to intensive droughts. It will take generations to bring back some version of the forests that existed before the British occupation. The Timbaktu Collective is one example of an organization creating a vision of combating desertification, restoring soil and managing shared ecological resources at a local level for the economic benefit of residents. Learn more at www.timbaktu.org.

Image credits: KCCA map (Dominio público under Creative Commons, text added to original map image); KCCA photos (Laura Short); Mary Vattamattam and Bablu Ganguly (one-world-award.com); Land cover infographic (Timbaktu Collective annual report 2017-18); KCCA waterway (timbaktu.org)