If you’ve ever seen orange and yellow foliage in the fall, bare trees in the winter, and new green leaves announcing springtime, then you’ve experienced the beauty of a temperate forest. Temperate forests make up 16% of the world’s total forest area. And like all forests, temperate forests play a vital role in ensuring the health of the planet.

Temperate Forest Characteristics

Temperate Forest Climate

Forests are generally classified by where they grow in the world. While tropical forests are in consistently warm areas near the equator and boreal forests are in consistently cold areas towards the poles, temperate forests are in the mid-latitude areas that are neither extremely hot nor cold. Temperate forests grow between 25° and 50° latitude in both hemispheres and are primarily found in parts of North America, Asia, and Europe.

Temperate forests began to emerge 65.5 million years ago in the Cenozoic Era. As the previously hot, wet climate became restricted around the equator and temperatures cooled at increasing latitudes, the mid-latitude temperate areas became more seasonal and life in these regions had to adapt or die.

Temperate Forest Plants

The most obvious component of any forest plant life is trees. Temperate forests can be further divided into two categories based on the type of trees that grow: deciduous trees and coniferous trees. Deciduous trees, also called broad-leaf trees, have wide, flat leaves that change color and drop in the fall. Some examples of deciduous trees in temperate forests are oak, elm, ash, and beech.

Coniferous trees in temperate forests have needles rather than leaves. Coniferous temperate forests have milder winters that don’t require shedding foliage seasonally and so are sometimes called evergreen forests. Pines, firs, and spruce trees are conifers. Mixed temperate forests have both types. Generally in the US, temperate deciduous forests are to the east and experience four distinct seasons. Temperate coniferous forests are to the west, where the rainfall is more erratic and the seasonal temperature differences are less pronounced.

Temperate Forest Animals

Due to their varied climate, temperate forests are home to a diverse range of amphibians, birds, insects, and mammals.

Temperate Forest Amphibians

Common amphibians are frogs, toads, and salamanders. Wood frogs, native to the United States and Canada, live in forests and breed in woodland pools or water-filled ditches. Fascinatingly, this frog species has been shown to recognize siblings and to group according to family.

Temperate Forest Birds

Migratory songbirds account for up to 75% of all bird species in deciduous temperate forests. In the spring and summer, these crucial breeding grounds come alive with the birdsong of species like the Wood Thrush and Cerulean Warbler.

Insects In A Temperate Forest

Common insects in the forest are bees, beetles, ants, walking sticks, moths, butterflies, and some dragonfly species. Insects play an important role in forest ecosystems but some insects, like bark beetles and budworms, can have negative effects when their populations swell to damaging levels, causing significant numbers of host trees to die.

Temperate Forest Mammals

Mammal species common to temperate forests include deer, timber wolves, bears, mountain lions, squirrels, rabbits, and skunks. Moose can also be found in mixed forests in colder climates. Least weasels, the smallest carnivorous predators in the world, can live in multiple habitats including temperate forests.

Mammal species common to temperate forests include deer, timber wolves, bears, mountain lions, squirrels, rabbits, and skunks. Moose can also be found in mixed forests in colder climates. Least weasels, the smallest carnivorous predators in the world, can live in multiple habitats including temperate forests.

How Do Animals Survive in the Winter?

Wildlife in temperate forests are notable for their seasonal adaptability. Spring, summer, and fall teem with life but the cold, dark winters can be difficult to survive. Many of the bird species are migratory and move to warmer climates for the winter. Some bird species that brave the winter, like owls, enter torpor, an energy-conserving inactive state. Other animals hibernate in the winter – bears are the largest predator in temperate forests. Certain species are active all winter, like deer who feed on bark and any plants that retain their leaves year-round. Some insect species in temperate forests can’t survive the winter but lay eggs that hatch come spring.

Human Impact on the Temperate Forest

The biggest threat to temperate forests may not be what you think.

Temperate Forest Deforestation

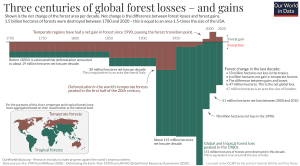

Unlike rainforests which are facing devastating deforestation rates year over year, temperate forest land cover has actually had a net gain since 1990. Historically, humans have relied on temperate forests for timber and biofuel. Large areas of temperate forests were also cut down for agricultural and urban expansion. However, as demand for wood as a fuel source decreased and agricultural practices became more efficient, many countries with temperate forests were able to restrict deforestation and transition to reforestation, allowing forests to regrow and expand.

Climate Change Effects on Temperate Forests

Climate change, fueled by humans, does cause increasing risk to temperate forests and the life that calls these habitats home. Extreme weather associated with climate change may lead to drought in some areas and to flooding in others. Warming temperatures can hasten snowmelts, changing the seasonal availability of water in temperate forests. Climate change can also intensify forest disturbances, like insect outbreaks, invasive species, and wildfire.

Conclusion

The temperate forest biome is one of the world’s major habitats and supports many forms of life, including our own. While life in temperate forests has largely evolved to be seasonally adaptable, climate change threatens to create unsurvivable extremes for these complex habitats. So the next time you take a stroll through a temperate forest to appreciate crunchy autumn leaves or marvel at a lush green spring, remember that it’s vital to the health of the planet that we continue to mitigate the effects of climate change and protect temperate forests.

Image credits: Girls in autumn forest (Photo by Vitolda Klein on Unsplash); Wood thrush (Wood Thrush Singing by Danielle Brigida is licensed under CC BY 2.0); Least Weasel (Least Weasel by Joachim Dobler is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0); Graph (Three centuries of global forest losses – and gains by Our World in Data is licensed under CC-BY 4.0)