Globally, thirty percent of all food made for human consumption, a staggering 1.3 billion metric tons of food, is either lost or wasted every year. On a planet where 690 million people go hungry each day, agriculture emissions fuel climate change, and where the COVID-19 pandemic is increasing food insecurity, reducing food loss and waste is critical for social, economic and environmental progress and well-being. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 12 aims to cut food waste by half by 2030 and reduce food losses.

Globally, thirty percent of all food made for human consumption, a staggering 1.3 billion metric tons of food, is either lost or wasted every year. On a planet where 690 million people go hungry each day, agriculture emissions fuel climate change, and where the COVID-19 pandemic is increasing food insecurity, reducing food loss and waste is critical for social, economic and environmental progress and well-being. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 12 aims to cut food waste by half by 2030 and reduce food losses.

But it’s important to recognize that food loss and food waste are not the same thing. The key difference between what is considered food loss and food waste is based on when the problem occurs along the food’s journey from farm to consumer.

While exact definitions and metrics for measuring food loss and food waste can vary by organization, certain themes are universal. Let’s take a look at the big differences between food loss and food waste and how the pandemic has exasperated both issues.

What is Food Loss?

Food loss happens earlier in the supply chain, before food reaches the consumer. This can be during growing, post-harvest, processing, or transportation stages. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), defines food loss as a “decrease in the quantity or quality of food resulting from decisions and actions by food suppliers in the chain, excluding retailers, food service providers and consumers.” (SOFA, 2019) This means that before even reaching store shelves, restaurant kitchens, or people’s homes, food becomes inedible for humans or is discarded along the way. This happens for many reasons.

Food loss can first happen directly on the farms, as damaged crops don’t yield enough, they spoil in the field, or are not harvested. Poor crop planning, bad weather, lack of efficient farming technology, growers choosing not to harvest food (due to price fluctuations in the market) or not enough workers to harvest food are some of the reasons food is lost before or at harvest time. While comprehensive global data is still in the works, previous estimates suggest that around 30 percent of the world’s food is lost at the farm level, and in the U.S., groundbreaking studies show similar estimates.

When restaurants abruptly shut their doors in Spring 2020 from COVID-19 lockdown orders, many farms suddenly found themselves with a surplus of food, as food demand from restaurants froze. Without buyers, some farms resorted to destroying large amounts their food. (It’s worth mentioning that many partnerships between farms have also helped divert their surplus food to food banks, pantries, and other needed areas.)

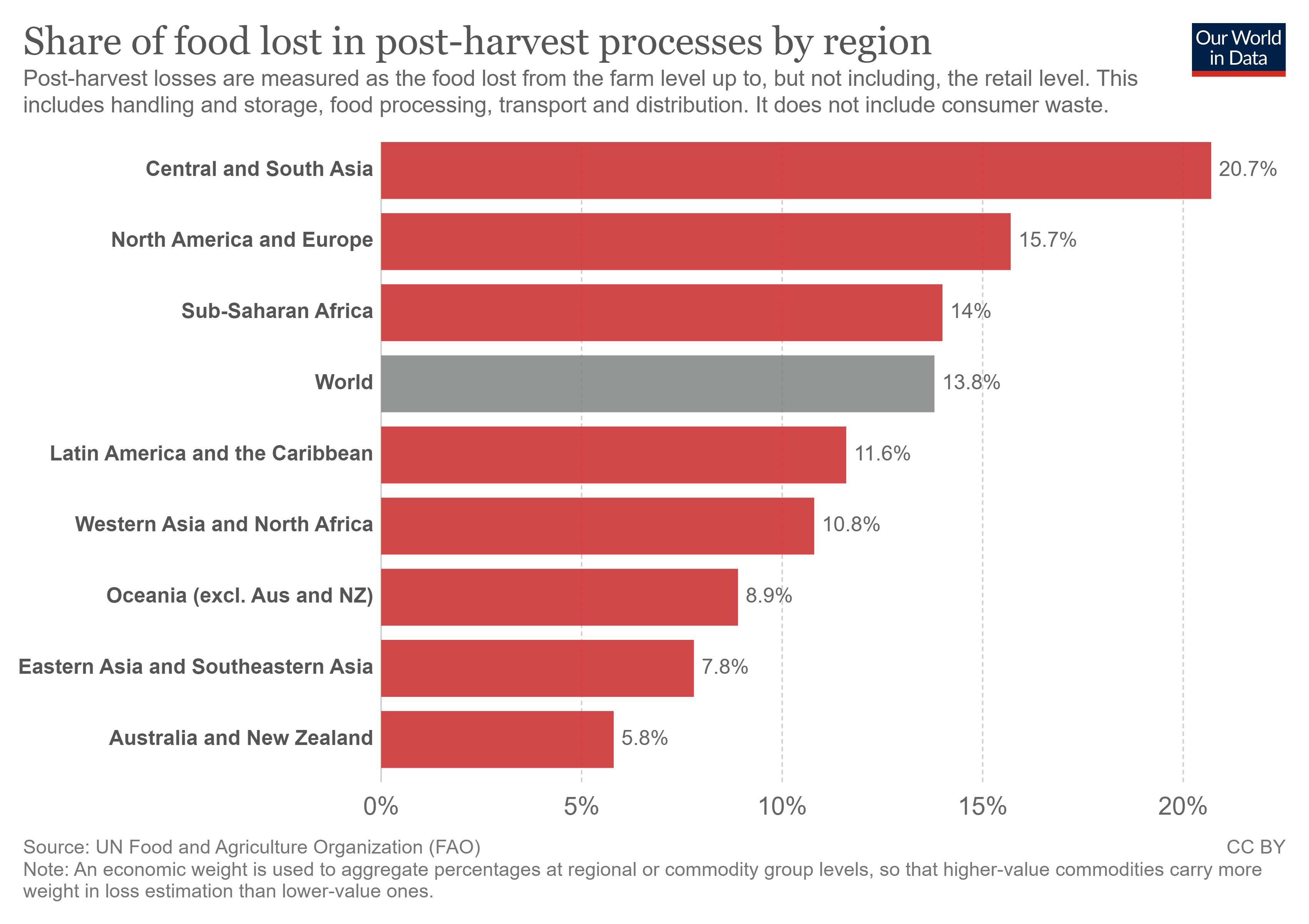

However, once food makes it past the farm’s harvest, inadequate storage and transportation can become an issue. For example, if food is not kept properly chilled and protected from pests and vermin while being shipped from place to place, it can be lost. Storing food for too long, often due to limited transportation availability, is another problem. Globally, 14 percent of food loss and waste happens post-harvest but before it makes it to retail shelves.

Since food loss can happen at various points before reaching consumers, different solutions are needed to addressing problems at different stage of the journey. As the COVID-19 pandemic shut down borders and disrupted the labor market, delays in shipments and reduced worker capacity created bottlenecks that meant more spoiled and lost food.

The Food Loss Index (from FAO) is a new measurement to help the world better understand the extent of its food loss. It compares the percentage of food lost by country, for a basket of 10 main commodities, with a base period. This is how the UN is monitoring progress on the Sustainable Development Goal 12 target of reducing food loss by 2030.

What is Food Waste?

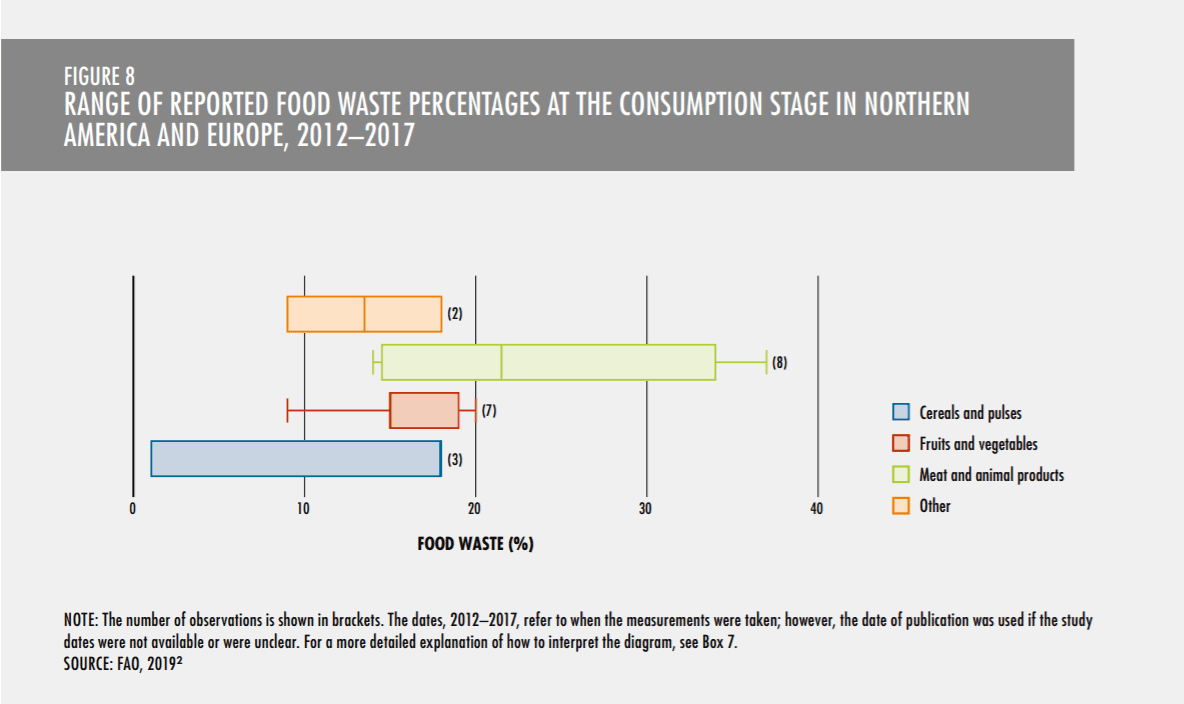

Food waste happens at the end of the supply chain, once it’s with consumers – this includes individuals, restaurants, grocery stores, markets, and cafeterias. Discarding food, either before or after it’s spoiled, is a key part of food waste. It happens when a restaurant serves a large portion and the customer eats half of it, tossing the rest. Or a head of lettuce sits forgotten in a fridge, and spoils. Or when a grocery store overstocks its shelves to maintain display aesthetics. FAO defines food waste as “the decrease in the quantity or quality of food resulting from decisions and actions by retailers, food service providers and consumers.” Food waste is more prevalent in wealthier nations, with Australia and the U.S. wasting the most food per capita.

Where food waste ends up is another problem. In the U.S., only 6 percent of food waste in 2017 was composted. The rest is sent to landfills, where it makes up the single largest category of waste inside U.S. landfills, according to the EPA. As food waste rots in landfills, it produces methane, a major greenhouse gas and contributor to climate change.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, food waste at the household level is expected to dip, as less income from job losses and bare store shelves impact people’s ability to purchase larger quantities. More meticulous meal-planning during lockdowns could have also created less food waste, as people avoid overbuying. Surveys shows that households are more aware of food waste since the pandemic began, and are wasting less food.

Image credits: Share of food lost in post-harvest process by region by Our World in Data is licensed under CC BY 4.0; Bell peppers (Rithika Gopalakrishnan on Unsplash); Range of reported food waste (FAO. 2019. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. 39. Rome. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO)