In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly laid out 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030, and these goals are a global call to action to make strides on environmental, economic, and social indicators of equity and sustainability. Several of the SDGs are impacted by or are otherwise related to housing and urban development. To that end, lawmakers should consider how zoning reform, specifically upzoning, can align with progress on the SDGs.

What is Upzoning?

Upzoning refers to changes in zoning ordinances to allow for taller or denser development.

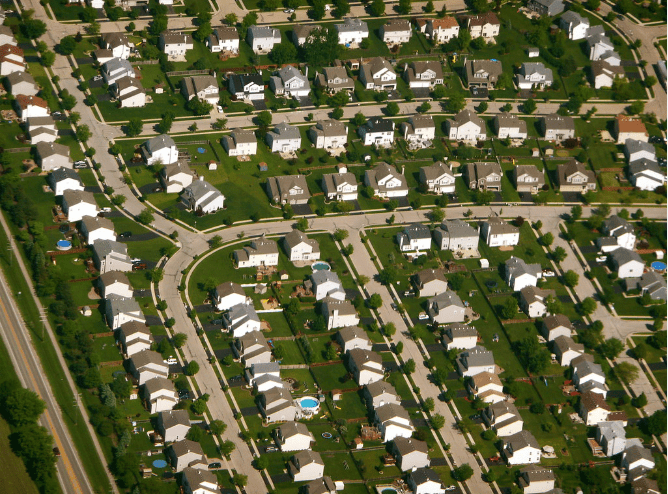

In the case of housing, zoning laws determine if a building can allow for multiple dwellings or if it may only be developed for single-family usage. These laws also specify the amount of parking that must be built to accommodate a building, the minimum lot sizes of these buildings, and how tall any development can be built. Restrictive zoning – i.e. mandatory lot and parking minimums, height limits, and single-family only zoned areas – reduces the total number of housing units that can be built in a certain area, leading to rising housing costs and suburban sprawl if housing demand in a city increases.

On the flip side, upzoning could reduce our carbon footprint, increase individual discretionary spending, and improve social equity in our communities, allowing us to make meaningful progress on a number of SDGs related to the environment, economy, and global society.

Understanding the Environmental Benefits of Upzoning

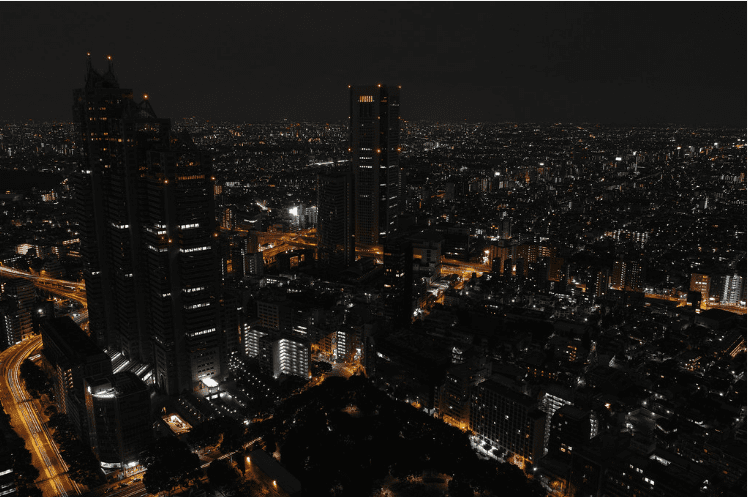

Lower carbon footprint in upzoned locations: The dense development of cities has a much smaller per capita carbon footprint compared to both rural and suburban areas – but especially compared to the suburbs. According to the Center for Clean Air Policy, the average family in a single-unit lot in the suburbs uses nearly three times as much energy on housing and transportation than the average family in an urban multi-family unit. Even eco-friendly suburban homes that drive hybrid vehicles, for example, still use nearly twice as much energy as their counterparts in urban multi-family housing. There are a number of reasons for this disparity.

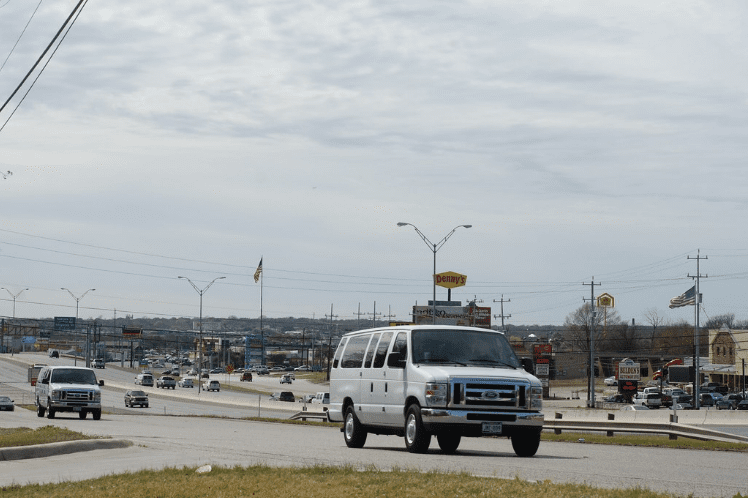

Housing units tend to be smaller in cities, which reduces the total amount of energy needed to heat and cool a home. Additionally, heating and cooling is more efficient in multi-family complexes than in detached, single-family homes. Multi-family complexes also use less water and energy on landscape and lawn maintenance. Urban communities are also more walkable and have better access to public transportation than the suburbs. This means fewer miles driven per person on a regular basis. This has the added benefit of reducing traffic congestion. Vehicles that run on fossil fuels are a primary source of outdoor air pollution and release nearly 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. If more affordable, medium-to-high density housing was available in cities – or if the suburbs upzoned to allow for denser housing – our collective time spent in cars would decrease significantly.

Fewer impervious surfaces: Denser development also reduces the total surface area of impervious surfaces. Impervious surfaces prevent rainwater from naturally soaking into soil. As water runs across sidewalks, parking lots, and roads, it collects pollutants along the way and deposits them into nearby bodies of water. This threatens aquatic wildlife that live adjacent to areas of human development. While densely developed cities will still have to contend with the consequences of impervious surfaces from their own development, fewer aquatic habitats in total will be threatened by runoff and development.

Less impact on wildlife habitats: Finally, city living reduces habitat destruction and fragmentation. Sprawling suburbs require more land to house people and more roads to keep people connected. All of this building causes habitat fragmentation, which is the process by which once continuous stretches of wild spaces are broken into smaller, isolated patches. Building up rather than out reduces suburban sprawl and as a result, minimizes the land area cleared for development.

Related SDGs: Responsible Consumption and Production (12), Climate Action (13), Life Below Water (14), Life on Land (15)

The Economic Benefits of Upzoning

Lower housing costs: According to a report from Freddie Mac’s Economic & Housing Research group, the United States housing market had a shortage of 3.8 million homes in 2020. Low inventory coupled with increased demand has caused housing prices to skyrocket. More than 20 million Americans have a rent burden that exceeds the recommended 30 percent of their pre-tax income on housing. Upzoning would help alleviate the housing shortage crisis by removing barriers that prevent additional market-rate units from being built. This would decrease housing costs, resulting in a positive chain reaction throughout the economy. Lower housing prices would increase disposable incomes, boost discretionary spending, and ultimately, help to stimulate the economy.

Access to Work: As people move back to urban areas to resume in-person work, we have an opportunity to improve the workforce’s geographical access to their offices. Upzoning would enable more young professionals to move to job centers for high-paying work. An influx of families to cities would bring additional tax dollars, spurring economic growth even further. Additionally, if commuters had better access to their offices, they would spend fewer dollars on high gas prices and automotive maintenance.

Access to Work: As people move back to urban areas to resume in-person work, we have an opportunity to improve the workforce’s geographical access to their offices. Upzoning would enable more young professionals to move to job centers for high-paying work. An influx of families to cities would bring additional tax dollars, spurring economic growth even further. Additionally, if commuters had better access to their offices, they would spend fewer dollars on high gas prices and automotive maintenance.

Related SDGs: Decent Work and Economic Growth (8), Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure (9)

Social Benefits of Upzoning

Access to resources: Upzoning provides more people with proximity to job opportunities, grocery stores, social services, and healthcare services. This is a function of access to public transportation as well as decreased distance between buildings. Access to necessities, along with the decreased cost of housing, would improve the material conditions of the lowest income communities.

Walkability: Dense neighborhoods are also more walkable. Current evidence suggests that neighborhood walkability improves mental health, creates a sense of community, and fosters social cohesion. By contrast, time spent in road traffic is positively correlated with higher rates of depression and anxiety. Presently, exclusionary zoning prevents the development that would allow denser neighborhoods from being built.

Improved housing equity: Finally, zoning reform could improve racial housing equity. Wealthy, white homeowners have historically used single-family only zoning as a means of enforcing racial segregation. This has created additional barriers to accruing generational wealth for people of color in America, especially for Black Americans. Empirical evidence shows that single-family only zoning reduces the number of rentals available in a neighborhood. The residents of these neighborhoods are disproportionately homeowners. Black Americans make up only 8.2 percent of homeowners in the United States and they hold only 5 percent of the wealth of their white counterparts. This reality enforces de facto segregation in neighborhoods predominately zoned for single-family only development. It follows that eliminating these restrictions would allow for more multi-family rental properties, thus setting the stage for racial desegregation.

Related SDGs: No Poverty (1), Zero Hunger (2), Reduced Inequalities (10), Sustainable Cities and Communities (11)

Development for A Sustainable Tomorrow

Both cities and suburbs have their role to play in making their respective communities more sustainable. The percentage of the world’s population that lives in urban areas is expected to grow from 55 to 68 percent by mid-century. Cities should incentivize housing developments to accommodate expected population growth – and to accommodate present-day commuters who would rather live closer to work. Without upzoning, cities will have limited ability to accommodate new demand. Meanwhile, suburbs can reform zoning ordinances to allow space for medium density housing and increase public transit options. These compromises can allow the suburbs to do their part without sacrificing the benefits of small town life.

Of course, upzoning alone will not fix all of the issues caused by sprawl and single-family only housing. However, it is a necessary first step towards creating a more sustainable future.

Image credits: : “A view from Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building Observation with DP1 Merrill” by Takashi(aes256) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; “Chicago suburbs from the air” by Scorpions and Centaurs is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; “San Antonio suburban sprawl” by Madellina Bird is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.