Evidence is the linchpin for effective argumentation. Without quality evidence, an argument falls apart. This is especially true for the scientific community which evaluates data constantly. We’ve already discussed the process of developing an effective argument. Students also need the skills to find the highest quality and most effective evidence to support their arguments.

Observational Evidence: Gathering Evidence Through Observation

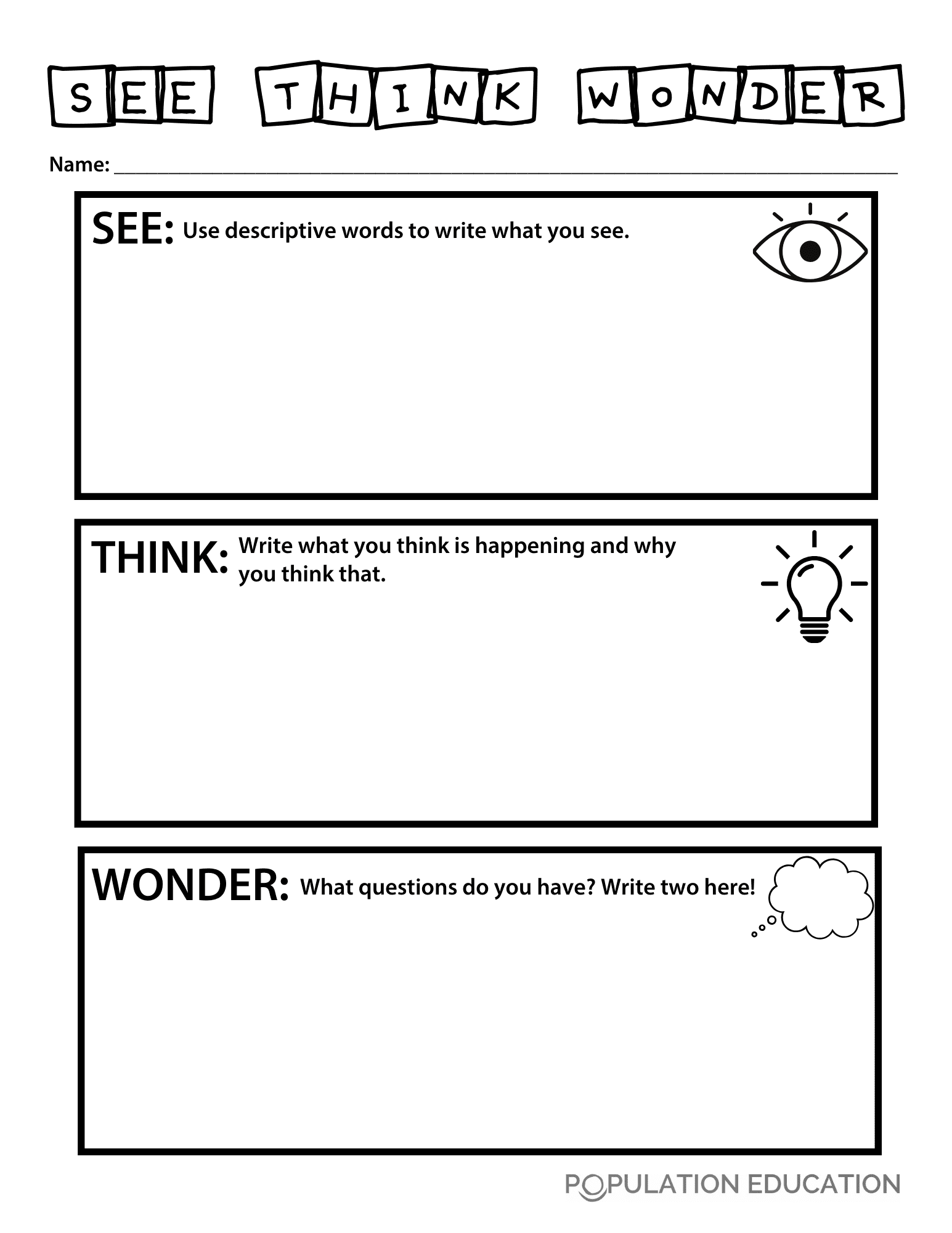

Students are often asked to gather their own scientific evidence in order to support an argument. Gathering evidence starts with observation – observation of an experiment, an object, an action, or a place. In order to generate quality evidence, students need to practice and hone observation skills. Add intentional and structured practice into your teaching with a simple “See, Think, Wonder” routine.

See, Think, Wonder: How to Apply This Thinking Routine

This often-used thought routine helps students practice observation and begin to use evidence-from-observation to build arguments for how the world works.

- What do you SEE? What details are observable? Colors? Shapes? Sizes? Movements? Changes? Are there patterns? Are there breakdowns in patterns or anomalies? This step is where we gather indisputable data about our topic, facts that we can all agree on.

- What do you THINK? Based on what you’ve seen, what do you think is going on? Take the details from the observation, and put them together to explain what might be happening, what it means, or which details might be related or connected. Here’s where we start to use the evidence from what we’ve seen to build a scientific explanation.

- What do you WONDER? Take what you’ve seen, and combine it with what you think about how it works, and wonder the big questions. How does this connect to the bigger world? What other mysteries come from the thing we’ve just observed? This step spurs creativity as students develop their own thinking and generate their own unique arguments and claims.

Get a downloadable See, Think, Wonder Worksheet now!

If you’d like a robust, structured version of a similar routine to try with your students, take a look at the BEETLES Project’s Nature Scene Investigator activity. It uses “I notice, I wonder, It reminds me of…” to help students explore a mystery object from nature. Along the way, students generate a ton of evidence from observation. They also practice scientific discussion and argumentation. The lesson includes a lot of teacher support with suggestions to help students observe deeper, question starters and ideas for encouraging discussion, and tips for how to pace the inquiry. Both the “I notice, I wonder, It reminds me of” and the “See, Think Wonder” thinking routines are especially great for elementary students who are new to making scientific observations.

Gathering Evidence from Outside Sources

Building an argument usually includes exploring what other people have to say about the topic. It can be difficult to sift through the mountains of information available to find the credible evidence needed to support a scientific argument. Facts might sound reasonable and authoritative, and might also be complete hogwash. Apply the handy CRAAP(!) test to evaluate the evidence you gather from other sources.

- Currency: Is the information recent, or has it been updated recently?

- Relevancy: Does the specific fact relate to your argument? Are there other facts that relate more closely? (more on this below!)

- Authoritative: Who wrote the information? What makes them an expert? What organizations are they associated with?

- Accuracy: Does the author use credible evidence? Has the info been fact-checked? What do other experts say about it?

- Purpose: What bias might the authors have? Why did they publish the info? Is their purpose clear? Where does their funding come from?

There are several great suggestions for lesson plans that put the CRAAP test into practice. This student-friendly infographic can remind them of the acronym. You can try one of the six CRAAP activities by Trevor Muir. Or you can try your hand at using the CRAAP test on one of these online sources from Kids Boost Immunity.

Evaluating Evidence: Picking Evidence to Best Support Your Argument

Once students have a wealth of evidence, they’ll need to pick the most compelling data to build their argument. Not all facts make solid evidence for an argument. Students need to use evidence that is high quality and minimizes assumptions. What does this mean?

Higher quality evidence is often based on greater amounts of data. For example, a group of students want to argue that a particular animal prefers their school’s parking lot. If multiple students see the animal in the parking lot on multiple days, their argument will be stronger than if only one student saw the animal once. Or if you’re conducting a science fair experiment, outcomes that occur lots of times make stronger data to support your hypothesis than outcomes that only occur once or twice.

High quality evidence should have minimal assumptions. Sometimes evidence is closely connected to the argument, and sometimes it is only slightly connected to the argument. When evidence is only slightly connected to an argument, the reader needs to make big assumptions to make it all fit. Let’s revisit the claim about the animal that prefers our parking lot. Imagine that we want to choose the best piece of evidence to support our argument: “the animal’s preferred food grows along the edge of the lot,” or “Juan saw the animal in the lot last Thursday.” The first evidence assumes that because the food is present, the animal will also be present and that it will prefer the lot. The second evidence assumes that since the animal was seen once, it prefers the lot. The first evidence makes a much greater assumption, and therefore is less likely and less compelling as evidence for an argument.

Give students practice comparing the quality of evidence and identifying assumptions with another BEETLES activity, Evaluating Evidence. Students will use a card sorting activity to evaluate different pieces of evidence to support the argument that “cheetahs are predators of wildebeest.”

Making the Strongest Scientific Argument

When we think of evidence, we often think of facts. Facts are supposed to be irrefutable nuggets of information: like that the sky is blue and that 1 liter of water weighs 1 kilogram on Earth. Students today are probably more aware than most that not all facts are true. It’s especially important to consider whether or not the facts that we use for our arguments are credible and effective. Teaching skills to help students gather quality, credible data that effectively supports their claims will lead to stronger scientific arguments.