Our industrialized world runs on rocks. Without the ability to bring specific materials from deep beneath our feet to the surface, sort out the valuable from the non-valuable, and manipulate it into usable parts, we would not have electricity, cell phones, internet, jewelry, pencils, and many aspects of daily life in a modern world. But the process of bringing these items to life has a cost.

Pinyon Plain Mine (formerly Canyon Uranium Mine) is a uranium mine about 10 miles from Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona. It’s a great place to explore impacts of mining in today’s world. The debate surrounding the mine’s operation touches on the economy, environmental issues, national security, Indigenous rights, and climate change, and highlights the complexities of energy consumption and resource use in our industrialized world.

Uranium Mining in the U.S.: A Brief History of Extraction and Industry Shifts

The birth of nuclear technology in the 1940s led to a boom in uranium mining in the U.S. New nuclear power plants and nuclear weaponry needed uranium ore, and the U.S. government encouraged widespread mining to meet the demand. The southwestern U.S., and the Navajo Nation in particular, sat on some of the largest deposits of uranium ore. Hundreds of mines and millions of dollars flowed into the region.

The uranium boom ended in the late 1970s. Soviet-US relations shifted, the need for new nuclear weapons declined, and new sources of cheaper and higher-quality uranium were found abroad. Public opinion of nuclear energy soured after a meltdown of the nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island in New York in 1979. Suddenly the global supply of uranium exceeded demand, prices plummeted, and all but ten U.S. mines closed down. The U.S. uranium mining industry lay quiet for several decades.

In 2007, uranium prices spiked for a short time. Countries like India and China were investing in nuclear power. When a mine in Canada flooded and put global supply at risk, U.S. miners reopened dormant mines and restarted domestic mining. Prices today are lower than the peak price in 2007, but remain profitable.

Demand for energy is expected to rise significantly in the coming years. Electric vehicles may make up as much as 40 percent of new car sales in the U.S. by 2030, and current electricity production may need to increase by 160 percent just to power AI data centers. Since fossil fuel power plants contribute significantly to climate change, there’s a push for nuclear power to fill the energy void. At COP28 in 2023, world leaders agreed to triple nuclear power capacity by 2050 in order to reach net zero carbon emission. The war in Ukraine highlighted a need for the U.S. to cultivate domestic sources of ore rather than buying ore from Russia. With rising clean energy demands, the demand for U.S. uranium seems like it isn’t going anyplace soon.

Canyon Mine: Uranium Extraction in Kaibab National Forest

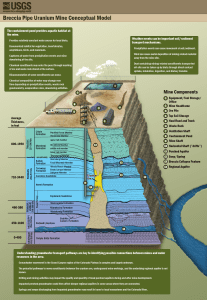

In 1986, the U.S. Forest Service approved plans for Canyon Mine to gather uranium ore in Kaibab National Forest. The uranium formed within vertical “pipes” of breccia rock below the ground. The mining plan included a vertical shaft sunk to a depth of about 1,400 feet. Horizontal tunnels would reach into the breccia pipe so miners could break up the uranium-rich ore, and an elevator system would bring the uranium to the surface. The ore would be stored in open-air pits on site until it could be transported to a mill for processing.

A Slow Start to Mining

Shortly after the mine’s approval, local communities protested its creation. The property sits in the shadow of Red Butte, the Havasupai Tribe’s sacred mountain. The Havasupai filed a lawsuit to stop the mine in 1990, but the suit was dismissed. There were several attempts in the coming years to ban mining in the region, including designating the Red Butte area as a traditional cultural property under the National Historic Preservation Act (2010), a mining ban on lands around the Grand Canyon by the Secretary of the Interior (2012), another lawsuit filed by Havasupai and the Grand Canyon Trust (2013), and establishing the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni- Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument on the land around the mine (2023). However, laws dating back to 1872 exempted Canyon Mine from any bans. Plans to develop Grand Canyon uranium mining continued.

Local challenges, combined with volatile prices, bankruptcy, and ownership transfer, meant that it took over 30 years to build the infrastructure needed to mine the ore. The current owner, Energy Fuels, purchased the mine in 2012 and completed construction on the buildings, containment ponds, and the mining shafts and tunnels. It wasn’t until January 2024 that mining actually began.

Environmental Impact of Uranium Mining: The Case of Canyon Mine

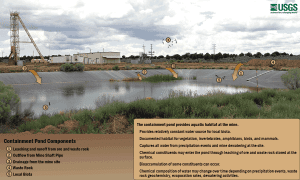

Water contamination from mining is one of the biggest concerns of this project. In 2016, Energy Fuels pierced an underground aquifer. Millions of gallons of water flooded the tunnels. The water tested high for uranium and arsenic. It was pumped (and continues to be pumped) to the surface where it filled open containment ponds. These plastic-lined ponds held the contaminated water where it could evaporate and where residue could be gathered and properly disposed of.

Energy Fuels argued that a layer of impermeable rock separated the mine from the deeper aquifers that supply drinking water to local communities and feed the Grand Canyon watershed. They said there is no risk of contaminated water moving beyond the mine. An EPA study released in December 2024 contradicted those assumptions, believing that underground fault lines are too complex to assume that contaminated water will not reach the Grand Canyon or drinking water sources. After the flooding, Canyon Mine was renamed Pinyon Plain Mine.

Local activists also worry about contaminated dust. The uranium rich ore is stored in open-air piles on the mining site before being transported. Nearby communities worry that dust will blow off the site and impact wildlife, soils, and the culturally significant Red Butte. Within the grounds, operators spray down the ore piles with water from the containment ponds to control the dust, and excess water flows back into containment ponds to evaporate.

Indigenous Rights and Uranium Mining: Historical Struggles and Modern Challenges

Besides pollution at the mine site itself, the uranium must be transported to a mill facility where it is refined. The only uranium mill in the U.S. is the White Mesa Uranium Mill in Utah, 250 miles away across Navajo Nation lands. The Navajo have a long and rocky relationship with uranium mining. The largest radioactive spill in the U.S. was on Navajo land: the Church Rock Uranium Mill Spill in 1979. For decades, the U.S. government suppressed knowledge of the harmful effects of radiation on people and the environment. And many Navajo have family and friends whose health has been directly impacted by uranium mining.

The first ore shipment crossed Navajo land in July 2024 without permission from the Navajo Nation. Protests broke out, and Energy Fuels stopped shipments until an agreement could be reached. A recent agreement means that shipments will resume in February 2025. Energy Fuels agreed to increased safety standards on shipments, to contribute to clean-up efforts at nearly 500 abandoned mines on Navajo land, and to pay the Navajo Nation per pound of processed uranium derived from the shipped ore.

Mining in Today’s World

Pinyon Plain Mine represents the intersection of many issues connected to mining today. The nuclear power industry continues to grow globally as nations look for carbon-neutral sources of electricity. War, national security, and politics drive the need for a domestic supply of uranium. And the mining industry brings needed jobs and economic security to communities in the region.

But uranium mining comes with a host of environmental and health challenges. A long history of exploitative practices still impact the Navajo, Havasupai, and other local communities. Fears exist about contaminants escaping the mine property and ending up in culturally sensitive areas, drinking water reservoirs, and in the Grand Canyon National Park. Energy Fuels complies with all permitting regulations but still has a long way to go to rebuild trust with local communities.

Energy is a necessary component of modern life, and uranium ore is one pathway towards creating low-carbon electricity. But deciding whether or not uranium mining is the best path forward means balancing the pros and cons of economy, national security, environmental sustainability, and cultural sensitivity.

Teaching About the Impacts of Mining

Explore some of these complex and interrelated mining issues with your own students in the lesson Mining for Chocolate. Cookies serve as mined land and chocolate chips represent ore that students extract using their mining tools – toothpicks. What will their cookie look like when mining is complete? How will the natural areas and communities near their mine be impacted? This fun mining lesson plan is free to download.

Image credits: Booklet (Atomic Energy and Peace. Bell Telephone Laboratories. 1954. Booklet archived by the Nuclear Museum and used with permission); Mine conceptual model (“Breccia Pipe Uranium Mine Conceptual Model” by The United States Geological Survey is public domain); Containment pond (“Detailed diagram of a containment pond at a mine site” by The United States Geological Survey is public domain); Red Butte (APK, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)