Last week, we discussed the origins of the modern American conservation movement and how it tends to be exclusive. In this blog post, we build on that discussion and explore how we can make U.S. conservation more inclusive of all people.

Conservation is all about humans interacting responsibly with nature so that the natural world can continue to nourish generations to come. We’ve seen how irresponsible resource use can bite us right back in the form of floods, hurricanes, crippling heat, and more. Because mainstream American environmentalism has had such a narrow portrait of who the classic conservationist is and what they care about, we’ve missed many opportunities and developed blindspots that impede the growth of a larger and more effective movement.

As we grow more deeply entrenched in the ongoing climate crisis, it’s more important than ever for everyone to be on the same team and able to contribute meaningfully to conservation efforts. Here are some (non-exhaustive!) ways we can expand the American conservation movement to be more inclusive – and thus also more effective.

Think Beyond the Poster Child of Conservation

Associating conservation primarily with hiking, kayaking, or rock climbing is undoubtedly cool, but it leaves many people out. Outdoor adventures can be inaccessible and prohibitively expensive for many. So, it’s important to reassess our instinctual ideas about conservation. A Cornell University survey found that racial minority and low-income participants had broader understandings of environmental issues; they stated that their top environmental concerns were societal – like poverty, inequality, education, and racism – rather than directly ecological topics like pollution or species extinction. Let’s widen the discourse on conservation to include social aspects that are more relevant to greater groups of people.

Address Social and Environmental Injustices

Racist policies and practices in housing, economic opportunities, and waste management, among many other social sectors, have left a disproportionately heavy impact on Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities in the U.S. Due to lower fines and less media attention, government agencies and private companies alike are apt to pollute and dump waste in poorer communities. The resulting health impacts are astonishing. Black Americans are 75% more likely to live near oil and gas facilities, which produce toxic air pollution, and Black children are twice as likely as their peers to develop asthma. As another example, Native American reservations have long been used as nuclear testing sites and dumping grounds for nuclear waste, exposing tribes to one of the most dangerous materials known on Earth.

For marginalized communities subjected to environmental racism, the existing conservation rhetoric of enjoying nature’s beauty probably doesn’t apply.

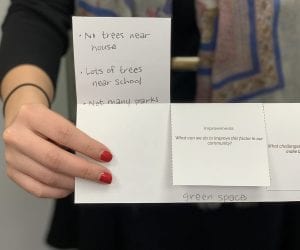

Make Communities Greener

People of color are far more likely to be deprived of nature, due largely to historical systemic injustices. In addition, new immigrants often prefer living in cities – many of which don’t have easy access to nature – because of greater job opportunities and community support. However, good regional planning can help. Urban and community green spaces can make residents healthier, foster stronger social relationships, and expose people to the benefits of conserving nature. Good public transit systems can also facilitate access to green space.

Break Down Barriers to Engaging with Environmental Issues

Academic jargon and ambiguous terminology can make conservation issues incomprehensible. Communicating simply and effectively makes a world of difference in engaging the public!

We also need to break down barriers to education and jobs in science, parks, and recreation. Despite small gains recently, women, racial minorities, and people with disabilities are deeply underrepresented in STEM fields. In addition, people of color often report feeling unsafe or being subjected to racial discrimination in public parks. Women and queer folks can also feel wary of sparsely populated natural settings, and those with physical disabilities may find nature inaccessible altogether.

Expanding free or low-cost environmental education programs for youth and adults, as well as improving educational equity more broadly, is a good place to start. Building staff and leadership who understand the unique concerns of underrepresented Americans is also critical to diversifying the field. To further prevent biases and hostilities, conservation organizations should consider mandating DEIJ training for all staff – and ideally also park visitors and other stakeholders.

Learn from Indigenous Knowledge and Practices

While the modern American conservation movement gained nationwide traction thanks to outdoorsmen, other important environmentalists in American history often get lost in the narrative. For many Indigenous American communities, conservation was never a paradigm shift. Many consider humans and nonhuman nature alike to be living beings, and living sustainably has long been a given. Native Americans responsibly stewarded the land for far longer than the U.S. nation has even existed, and there’s much to learn from them. In doing so, it’s also important to work through conservation’s complicated history with Indigenous people – such as the desire to protect nature by pushing Native Americans off of their ancestral lands.

Teach Conservation with PopEd

All in all, conservation has done a lot for Americans and our lands. But good can always be better! Meaningful environmental action requires inclusion and cooperation. Expanding conservation can and should begin with youth education, and PopEd is the perfect place for teachers to find lesson plans, supplemental materials, and blog posts that incorporate conservation education into classrooms of all kinds.

Image credits: Climate strike (Climate Justice by Fred Murphy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 1.0); Landfill waste (ID 522257175 by zeljkosantrac); Environmental education (Bird Bingo! by USFWS Pacific Southwest Region is licensed under CC BY 2.0)