The population story of the United States involves constant growth and movement. From our founding, we’ve been a nation of immigrants. But we’re also a nation of internal migrants, moving around our vast land by the same push/pull factors that drive people across borders and oceans. Push/pull factors within the U.S. include economic hardship/opportunity, social unrest/safety, persecution/justice and environmental peril/stability. At times, these forces have led to large migration waves of entire communities, and specific demographic groups.

Let’s explore six of the most notable shifts in U.S. population geography: from westward expansion in the 19th century, to the post-WWII suburban shift in the 20th century, to the new great migration of the 20th and 21st centuries.

1. Westward Expansion

The American Revolution ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which granted independence to the original 13 states, as well as control of additional territory that extended from the Appalachian Mountains west to the Mississippi River. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 nearly doubled the size of the United States and the new land beckoned pioneers. By the middle of the 19th century, treaties with Great Britain, Spain, and Mexico expanded the U.S. territory to the Pacific Ocean, and people continued to move westward.

“The Covered Wagon of the Great Western Migration. 1886 in Loup Valley, Nebr.” A family poses with the wagon in which they live and travel daily during their pursuit of a homestead. (National Archives Catalog)

Why Did People Move West During Westward Expansion?

For White settlers, this migration was encouraged by the pull of free land, jobs (in ranching, logging and mining), and sometimes the prospect of riches in gold and silver. The Homestead Act of 1862 accelerated western settlement, providing free ownership of 160 acres to would-be homesteaders who cultivated public land for five years. Eventually, 10 percent of the U.S. landmass was given to homesteaders, most of it west of the Mississippi River.

How Did Westward Expansion Affect Native Americans?

This westward expansion came at the expense of Native American tribes who were forced from their ancestral lands. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the forcible displacement of thousands of Native Americans from their homes in the Southeast. That was followed by the Indian Appropriations Act (actually a series of acts over several decades) that resettled tribes onto reservations and opened up even more of their lands to White settlement.

Westward Expansion Quickly Changed the Landscape

A Harper’s Weekly article describes the mad dash to settle a new Oklahoma town after new land was opened to homesteaders with the 1889 Indian Appropriations Act:

“At twelve o’clock on Monday, April 22nd, the resident population of Guthrie was nothing; before sundown it was at least ten thousand. In that time streets had been laid out, town lots staked off, and steps taken toward the formation of a municipal government. At twilight the camp-fires of ten thousand people gleamed on the grassy slopes of the Cimarron Valley, where, the night before, the coyote, the gray wolf, and the deer had roamed undisturbed.”

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 also hastened the westward movement of the U.S. population. By 1900, there were nearly 200,000 miles of railroad lines crossing the country.

2. The Great Migration

Part of the Great Migration, Scott and Violet Arthur pose with their family after arriving in Chicago in August 1920, two months after their two sons were lynched in Paris, Texas.

Why Did The Great Migration Happen?

The end of the Civil War and slavery was followed by a brief period of opportunity for Black residents in the South known as Reconstruction (1865-1876). The presence of federal troops in southern states kept the peace and protected the civil rights of former enslaved people that were granted with the passage of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments. Reconstruction abruptly ended with the Compromise of 1877, in which Southern Democrats (who favored segregation) agreed for Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to be installed as President as long as federal troops withdrew from the South. This enabled southern states to enact Jim Crow laws to segregate, intimidate, and discriminate against Black citizens for nearly a century until the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s. Oppressive, and sometimes violent, conditions under Jim Crow laws (push factors) and the hope for better jobs and fairer treatment in the North and West (pull factors) brought about an unprecedented migration of Black Americans out of the South, known as The Great Migration.

When Was The Great Migration?

Taking place from the 1910s to the 1970s, The Great Migration had two distinct waves. From World War I through World War II, job openings in industries in northern cities (New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland) drew some 2 million Black migrants from the agricultural South. In the post-World War II era, 3 million more left the South for both northern and western cities, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, Portland, and Seattle. At the beginning of the 20th century, 9 in 10 Black Americans resided in the South. By 1970, the South was home to just over half of the nation’s Black population.

While they had left Jim Crow behind, these new migrants often faced housing and employment discrimination in their new cities, as long-time residents often resented the rapidly-changing demographics. A masterful telling of this period through oral histories, is found in Isabella Wilkerson’s award-winning book, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration.

In all, 7 million Black people left the South during the 20th century, in addition to 20 million Whites. Together, these groups comprised a Southern Diaspora of movement North and West in search of better economic opportunities.

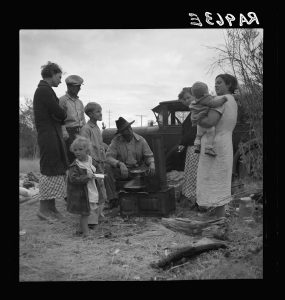

3. The Dust Bowl Exodus

Part of this Southern Diaspora was fueled by the environmental collapse and resulting poverty of the Dust Bowl, a period of unrelenting drought and dust storms in the Plains (1930-1936) during the Great Depression, affecting parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico.

What Was The Dust Bowl?

The Dust Bowl is considered one of the worst man-made ecological disasters in U.S. history, as the drought conditions were exacerbated by poor farming practices. It produced more than economic hardship – the inhaled dust particles infected and killed thousands with “dust pneumonia.” Others suffered from starvation as farmland turned to desert. In one storm day alone, known as Black Sunday (April 14, 1935), as much as 3 million tons of topsoil were estimated to have blown off the Great Plains.

The Dust Bowl Migration

Roughly 2.5 million people were forced to leave their homes and farms behind as a matter of survival. Over 200,000 made their way to California to pick grapes and cotton in the fertile San Joaquin Valley for poverty wages, replacing tens of thousands of Mexican migrants who had been repatriated. Most of these migrants lived in makeshift communities of tents and shacks with no plumbing or electricity. They faced discrimination and harassment from the locals, who derided them as “Okies,” regardless of what state they had come from. The plight of these Dust Bowl migrants is captured in John Steinbeck’s classic, The Grapes of Wrath (1939), a novel tracing the journey of the fictional Joad family from Oklahoma to California.

Roughly 2.5 million people were forced to leave their homes and farms behind as a matter of survival. Over 200,000 made their way to California to pick grapes and cotton in the fertile San Joaquin Valley for poverty wages, replacing tens of thousands of Mexican migrants who had been repatriated. Most of these migrants lived in makeshift communities of tents and shacks with no plumbing or electricity. They faced discrimination and harassment from the locals, who derided them as “Okies,” regardless of what state they had come from. The plight of these Dust Bowl migrants is captured in John Steinbeck’s classic, The Grapes of Wrath (1939), a novel tracing the journey of the fictional Joad family from Oklahoma to California.

4. Moving to the Suburbs

World War II industries brought the U.S. out of the Great Depression. The post-World War II Era led to more jobs in manufacturing that moved many out of poverty, and made car and home ownership attainable for a larger segment of the U.S. population. With cars came more roads and interstate highways, and more construction of communities on the outskirts of cities. This explosion in suburban development and the growing size of families spurred by the post-war Baby Boom (1946-1964) drove migration of middle-class households from cities to suburbs across the country. In 1940, fewer than 20 percent of the population resided in suburban areas. That grew to 30 percent by 1960 and to over 50 percent today.

There was also a racial component to this movement to the suburbs, sometimes referred to as “White flight.” As Black residents moved into cities from The Great Migration, White residents tended to move out, creating de facto segregation even in the “desegregated” North.

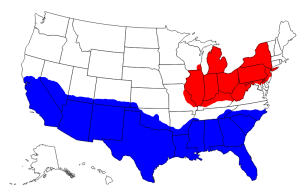

5. Rustbelt to Sunbelt

Map of the Rust Belt (red) and Sun Belts (blue)

The final decades of the 20th century started a new wave of migration from the Northeast and Midwest to the South and Southwest that continues today. Once booming manufacturing hubs began losing jobs to overseas markets due to new international trade agreements that enabled companies to produce goods more cheaply in other countries. This created “Rust Belt” states, characterized by shuttered factories and declining population. At the same time, states in the southern tier (from California to Florida) drew migrants with mild climates, affordable housing, low taxes and new jobs in technology, defense, energy production and aerospace. Today, 12 of the 15 fastest growing U.S. cities are in this “Sun Belt.”

This summer, Phoenix, Arizona recorded over 100 straight days of temperatures of 100°+, but this hasn’t stopped the allure of the Southwest. Even so, climate change is affecting the Sun Belt in ways that might eventually cause a reverse migration – extreme heat, flooding of low-lying areas, wildfires, and landslides. The population growth of these popular areas has also strained limited water resources, especially in areas dependent on the Colorado River.

6. The New Great Migration

Once the Civil Rights Acts (1964, 1965 and 1968) mandated fair treatment for Black residents of the South, some of the children and grandchildren of The Great Migration began to return to the area. This reverse migration accelerated starting in the 1980s with the deindustrialization of cities in the North and Midwest that had drawn Black migrants earlier in the century. Cities of the “New South” including Atlanta, Nashville, Charlotte, and Houston drew Black professionals to their booming economies and closer to extended families. This “New Great Migration” has grown the Black middle class in urban areas throughout the southeast U.S. In 1970, Atlanta had the nation’s 13th largest Black population. By 2010, it had surpassed Chicago to rank second (after New York) in Black population size. The Black population more than doubled from 1990 to 2020 in Charlotte, and topped 1 million in the Houston and Dallas areas for the first time.

The Story of U.S. Migration

Internal migration within the U.S. was at a high in the post-World War II years (about 20 percent). Back then, the population was younger, more mobile, and more likely to rent rather than own homes. In recent decades, this rate of movement has gradually slowed to less than half of what it was 60 years ago as our population has aged. The U.S. population story continues to unfold and unforeseen push/pull factors may propel migration in new directions, just as they have throughout our history.

Do you want to learn more about current trends in internal migration in the U.S.? Check out our blog post on how internal migration is shaping the U.S. population.

Image credits: Family in covered wagon (Photograph of a Family with Their Covered Wagon During the Great Western Migration is Public domain, via National Archives Catalog); Arthur Family during the Great Migration (undetermined; published in The Chicago Defender on September 4, 1920 is Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons); Dust bowl refugees (Along the highway near Bakersfield, California. Dust bowl refugees by Dorthea Lange is Public domain, via Library of Congress); Rust and Sun Belts (Ejrms, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)